You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

A fateful day at the Kline mine

On March 23, 1959, an explosion at the Phillips-West Mine at Brimstone had killed nine people, making it the deadliest mining disaster in Scott County’s history.

That tragic day had brought together the Phillips-West Mine and the C.L. Kline Mine, which was located just two miles away. Audie Acres, foreman of the Kline Mine, had been one of the first on the scene at the Phillips-West Mine after the explosion occurred that morning, and helped lead the search for survivors.

As the community mourned the tragedy at the Phillips-West Mine, no one could have imagined that another tragedy awaited at the nearby Kline Mine just six years later.

Audie Acres, the man who was noted by the U.S. Bureau of Mines as a hero in the aftermath of the Phillips-West Mine explosion, along with George Lewis and Jack King, had died in 1964. C.L. Kline, the mine’s owner, served as its foreman in 1965.

Charles Lawrence Kline was a prominent businessman at Robbins before he was a coal-miner. He owned the C.L. Kline Store at Robbins. Born in 1907, he was the son of George Washington Kline and Ella Jeanette Thompson. He and his wife, Flonnie Davis, had three children, including George Litton Kline, who would become one of the most prominent physicians in Scott County’s history.

Kline had been at his mine on the morning of Monday, May 24, 1965. He had performed the usual inspection of the mine before the start of the work day, then left around noon to check on another mine he owned.

At 4:15 p.m. that afternoon, when the day shift miners would ordinarily emerge from the mine shaft to end their shift, and a new shift of workers would take their place, no one emerged from the underground cavern.

It was at 4:21 p.m. that Harlin Lewallen, a night shift miner who was arriving for work, noticed coal dust and “blown back” weeds at the entrance to the mine. He called for Kline, who had returned to the mine and was talking to two other night shift workers, Lead Bowling and Charlie Harvey.

It was immediately realized that there had been an explosion inside the mine. Later, a steel conveyor pan was found to have traveled 1,000 feet from the conveyor due to the force of the explosion.

An investigation by the Bureau of Mines determined that a mixture of methane gas and air had been ignited by a cigarette lighter. The explosion was propagated by coal dust to other areas of the mine, causing significant damage to the structure of the mine. Forces extended all the way to the surface, though they were dissipated by expansion in abandoned caverns inside the mine.

The volatile ratio of coal from the mine was 0.40, based on an analysis of coal produced by the mine. The Bureau of Surface Mines considered a volatile ratio greater than 0.12 to be explosive.

So while the nature of the coal was known to be explosive, the Bureau of Mines had classified it non-gassy. Three other mines within a four-mile radius were considered gassy, including the Phillips-West Mine, which had been reclassified after the March 1959 disaster there. But inspections at the Kline Mine had measured methane gas concentrations only from 0.03% to 0.15%.

Investigators never determined exactly what time the explosion occurred. However, evidence inside the mine and testimony from Kline nailed down the timeline to sometime between 1:30 p.m. and 3:45 p.m.

Kline, who had left the miners at around 11:30 a.m., had given his workers instructions to load coal from one of the side rooms in the mine. That had been done, a task that it was estimated would’ve taken at least 90 minutes to complete. The men’s lunch pails were all empty, indicating that they had taken their 30-minute lunch break. And the first men from the night shift had arrived outside the mine by 3:45 p.m., helping narrow the window the disaster could’ve occurred.

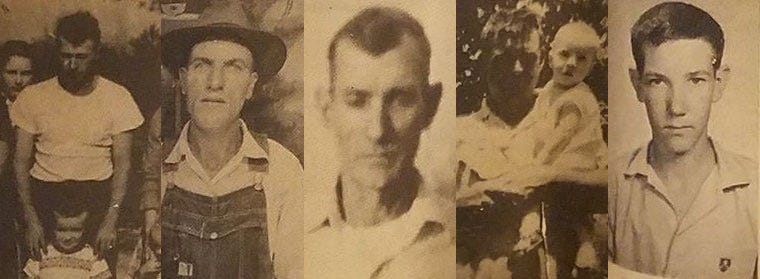

All five men inside were killed.

Nearly 1,000 people crowded around the mine as rescue efforts began. Unlike the Phillips-West Mine, which saw the bodies of nine victims recovered relatively quickly, the Kline Mine blast had collapsed portions of the mine, slowing down recovery efforts considerably. It took 36 hours for all five men to be reached.

In addition to state and federal mine inspectors, a seven-man crew from the Pocahontas Coal Company, the Scott County Rescue Squad, the Tennessee Highway Patrol, the Scott County Sheriff’s Department, other miners, and many volunteers showed up to assist with the recovery effort.

Five ambulances from Oneida Funeral Home and West Funeral Home were stationed outside the mine, and transported seven rescue workers to Scott County Hospital for treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning. Among the injured were Philmore Sexton, Clarence King, Gorman Young, George Honeycutt, Lloyd Sexton, Dewey C. Hatfield, and Cletus Boles.

Several other rescue workers were treated at the scene for issues ranging from minor carbon monoxide poisoning to exhaustion.

The mother of one of the mine victims was taken to the hospital by ambulance after collapsing.

Rescue workers reached the first body at 4:45 a.m. on Tuesday, May 25, 1965, some 12 hours after the rescue effort began. The first bodies brought out of the mine were Lawrence Griffith and Arthur Norris, at 3 p.m. on Tuesday, May 25, 1965. It was believed that they hadn’t been killed instantly, but that they had died of suffocation after the blast occurred.

Russell Webb, who had been stationed at a loading ramp in the mine, was brought out at 7:30 p.m. that Tuesday evening. He was found pinned beneath one of the coal cars.

At 3:15 a.m. on Wednesday, May 26, 1965, the last two miners were brought out: Phillip Davis and Clayton Griffith.

As the Bureau of Mines began its investigation of the tragedy, an investigating committee included C.L. Kline; Ben Smith, who was the foreman at Kline’s other mine; Chester Honeycutt, who was a maintenance man at the mine; Andrew West, president of the W&W Coal Company; and Jack King, the former superintendent of the nearby Laddie coal & Mining Company who had assisted with recovery efforts after the Phillips-West Mine disaster in 1959.

Investigators determined that the blast had originated near the face of the left air course entry. A cigarette lighter, open for lighting, was found in that area, and smoking materials were found on the body of one of the miners who was recovered from that area, leading investigators to conclude that the cigarette lighter had sparked the explosion.

While all nine victims from the Phillips-West Mine explosion were from the Oneida, Tunnel Hill and Paint Rock communities, the five victims of the Kline Mine explosion were all from Robbins.

Lawrence Ernest Griffith was 57, the husband of Oasie Hill. His children included Arnold Griffith, George Trumon Griffith, Kenneth Griffith, Kermit Griffith, Richard Griffith, and Doffice Lee Griffith. Kenneth was a U.S. Army soldier who had died in a plane crash just weeks before the mine disaster occurred. Both Lawrence and Kenneth are buried at Lone Mountain Cemetery.

Henry Arthur Norris was 49, the husband of Ada V. Foster. His children included sons Hubert Norris, Kenneth Norris, Jackie Norris and Wendell Norris, and daughters Shirley Newport, Joyce Fairchild, Janice Sexton, Judy Norris, Kathy Norris, Lela Norris and Denise Norris. He was buried at Reed Cemetery in New River.

Russell Webb was 47, the husband of Myrtle Huckeby. His children included Nola Faye Webb, Anna Louise Webb, Beulah Mae Webb, Margie Marie Webb, Estell Ardell Webb, Belinda Faye Webb, Buddy Webb, and J.L. Webb. He was buried at Griffith Cemetery at Glenmary.

Phillip Clarence Davis was 52, the husband of Carrie Norman. He had a son, Charles Vernon Davis. He was buried at Concord Cemetery in Robbins.

Clayton Griffith was 20, the son of Everett Griffith and Mary Ella Taylor. It was his mother who had collapsed during the rescue effort and was transported to the hospital.

By fate, three other miners were supposed to be inside the mine that day but had taken the day off. One of them was Everett Griffith, Clayton’s father. He took the day off to conduct chores on his farm. Also off were Nelson Harness and his son, Junior Harness. Nelson was sick, and Junior had driven him to a Knoxville hospital for treatment.

For the second time in six years, Scott County had been rocked by a fatal mine explosion. Collectively, the two explosions at the Brimstone mines claimed the lives of 14 Scott Countians.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The WeekenderThursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)