You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

The story of Francis Miller of No Business

The Miller family was not one of the Big South Fork region’s pioneer families. That distinction goes to families like the Slavens, the Burkes, the Blevinses and the Hatfields. The Slaven family has the distinction of being the first family to settle what we now know as the Big South Fork, with Richard Harve Slaven being granted land on the river from near the mouth of Bear Creek in Kentucky to near the mouth of Parch Corn Creek in Tennessee. The others followed closely behind. Other early families included names like Smith, Tackett and Young, though they didn’t flourish quite like the aforementioned families, whose descendants can still be found throughout the North Cumberland region today.

By the time Francis Miller was born on Nov. 2, 1856, the Big South Fork region was already beginning to thrive, with bustling little settlements in the creek bottoms of No Business and Station Camp. But, in time, he too would arrive on the river, and his family flourished in its own right. The mark of Miller isn’t engraved quite as deeply in the bottomland settlements as that of Slaven, Burke, Blevins or even Hatfield. But for a season, France Miller was one of the leading residents of No Business: a storekeeper, a postmaster, and the builder of the community’s first school.

Beginnings

Francis Marion Miller was born in Wayne County, Ky. on an early November morning in 1856. That was two days before James Buchanan was elected President of the United States, and a little less than five years before Civil War would rip the Big South Fork region apart at the seams.

France’s folks are believed to have migrated from North Carolina to the broader Big South Fork region, but there’s some question about their identity. Some family trees list them as Millican. Others — likely correct — list the father as Miller and the mother as Millican.

Their names are said to be Thomas (or Tommie) and Margaret Ann. That can be especially confusing because there is a Thomas Millican and family found in Wayne County, Ky. in the 1860 census. One of the children in his home: 5-year-old Francis M. Millican. However, that Thomas Millican — born about 1819 — was the husband of Mary Millican, not Margaret Ann. In fact, one of their daughters was named Margaret (born about 1836). The other children listed in their home in 1860 included William (age 21), Mary Jane (18), Celia F. (16), Susan, Martha Ann (12), John (10), Charlotte (8), Amanda, and William Riley (1). An older daughter, Katherine, was found in the 1850 census (age 23 at the time), when the Millican family lived in Whitley County, Ky. Ten years before that, in 1840, Thomas Millican lived in Anderson County, Tenn. with a wife and two children.

An old marriage record from Anderson County on March 18, 1839 lists “Thos. Millican” as marrying “Polly Miller.” Polly (Mary) was likely Mary Burke, a sister of Big South Fork pioneer Jonathan Burke, who is the ancestor of most Burkes found in Scott County today. Why she was recorded in the marriage book as Miller rather than Burke is anyone’s guess.

A best-guess attempt at that 1860 census record is to fast-forward to 1870. In 1870, Francis M. Millican is living in Scott County, with his age given as 14. He’s living with 37-year-old Margaret Millican, and other children that include William R. (10), Thomas J. (8), Polly (3), and James A. (3 months). The head of the house is Polly Millican (70). This would appear to be the same Frances, Margaret and William R. found in the home of Thomas and Polly in 1860. The obvious assumption, then, is that Thomas Millican and Mary “Polly” Burke were the grandparents of Frances Miller, and that Margaret, their unmarried 24-year-old daughter, was living with them in 1860 along with her two children, Frances and William Riley. By 1870, she had additional children Thomas J., Polly and James A. Thomas had died by that point, while Margaret and her children continued to live with Polly.

By that point, 1870, the Millicans were living in the Big South Fork region. Their neighbors included Rebecca Slaven, Jonathan and Nancy Burk, Elijah and Nancy Smith, Haden Burk and William Sweet — some of the common names from the late 19th century Big South Fork settlements.

The definitive answer as to the identity of France’s father may come in old hand-written birth records from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. In a book dated 1856, Frances M. Miller is listed as the son of William Miller and Margaret Miller. However, France’s death certificate, when he died in 1948, lists his parents as Thomas Miller and Margaret Miller.

There’s a Civil War pension record filed in 1880 showing that William Miller — husband of Margaret A. Miller — enlisted in the Union army and served in both the 3rd Kentucky Cavalry and the 5th Kentucky Cavalry. A separate record shows that his enlistment date was in 1865. A draft registration record shows that William Miller was born in 1830, and that he was married when he registered for the draft in Kentucky on July 1, 1863.

There’s no record that Margaret Millican ever married William Miller. She was living with her mother and her children, and going by Millican, when both the 1860 and 1870 censuses were taken. However, the 1880 census lists her as Margaret Miller, and her marital status is listed as “widowed.” That’s the same year she filed for a Civil War pension and identified herself as the wife of William Miller. Her children living at home that year included William R. (age 19), Jefferson (18), Polly (13), James (12) and Pharzina (7). Although each of the children (besides Pharzina, born after the 1870 census) were listed as Millican in the 1870 census, they’re listed as Miller in the 1880 census.

Frances Miller married Elizabeth Spradlin (1854-1920) on April 26, 1876. She was the daughter of Ambrose Spradlin (1827-1901) and Sarah “Salley” Foster (1835-1931) of Wayne County, Ky. Their marriage took place in Scott County, where France was living at the time. France’s name in the marriage record was recorded as “F.M. Miller” — additional proof that the Margaret’s children started going by Miller rather than Millican at some point just after 1870.

France and Elizabeth, or “Eliza,” had eight children: John Francis Miller, George Marion Miller, Mary Ann Miller Blevins (1884-1963), Reason Jefferson Miller (1887-1925), Laeuvada Miller (1893-1894), William J. Miller (1895-1980) and Victoria Miller Blevins (1898-1993).

Life at No Business

After moving to the Big South Fork with his mother and siblings just prior to 1870, France Miller continued to make a life in the No Business settlement as he and Lizzie raised their eight children. He would spend the remainder of his life at No Business.

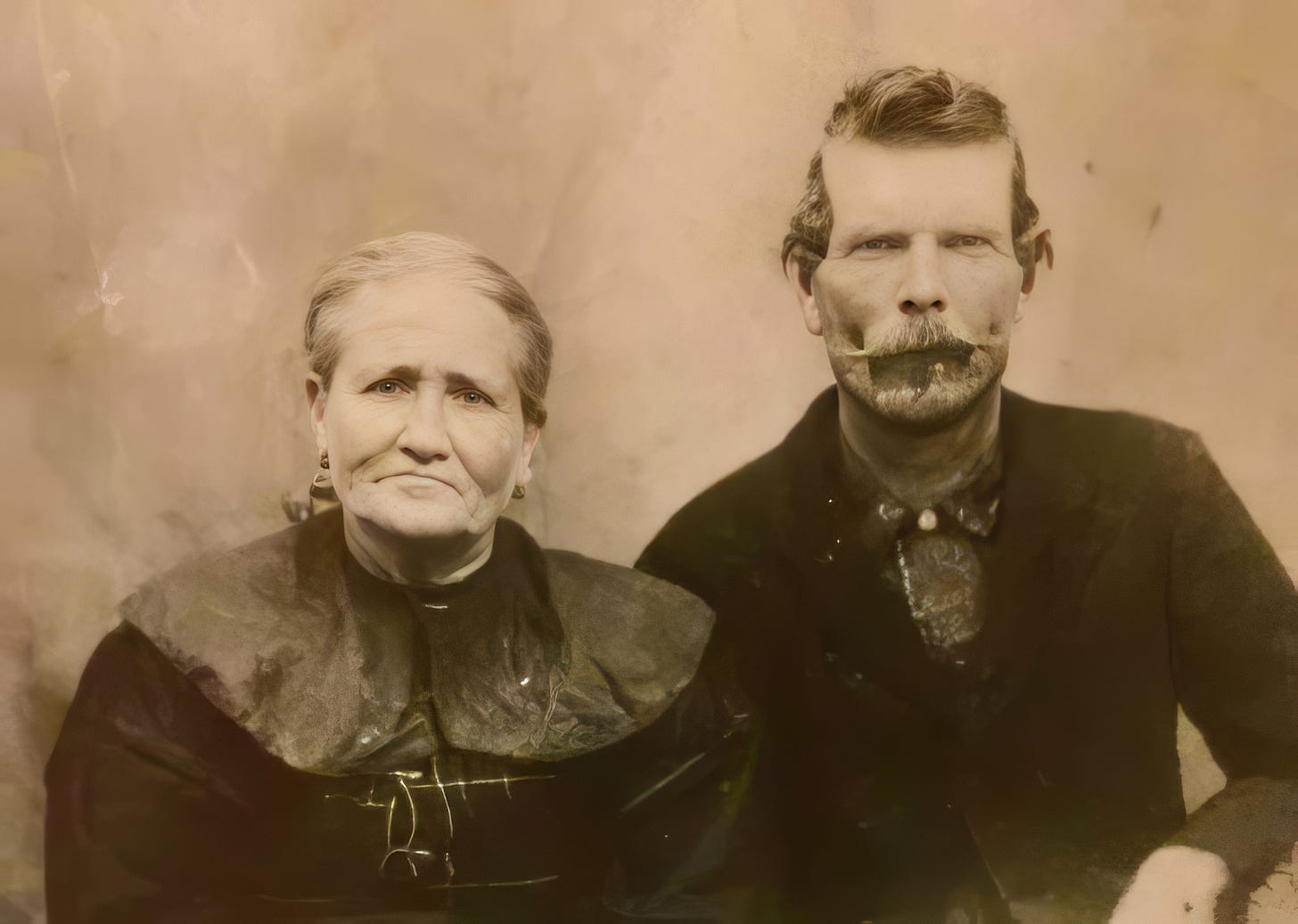

France Miller was a red-haired man with a large, handlebar mustache who became one of the most respected citizens of No Business. He built a general store near the mouth of the creek, where it empties into the Big South Fork River, and also served as the postmaster of Elva. (The first postmaster there was Lewis Burke.) It has been written that he built the first school at No Business, as well.

Just prior to 1900, Miller purchased the home of Jonathan Burke — his great-uncle — and moved it from Duck Shoals to his property at No Business. The Burke home, located just below Parch Corn Creek, had been the site of the Battle of No Business in 1863, after a company of rebel soldiers had holed up there for the night after spending a day raiding farms on Station Camp Creek and Parch Corn Creek. Members of the Scott County Home Guard — including several members of Burke’s family — surrounded the cabin that night and opened fire on the Confederates, killing them all.

Following that battle, the Burke family moved out of the home, haunted by the events that had occurred there. The home was vacant for several years before being purchased by George Pennington, who in turn sold it to Miller. Miller disassembled the home and moved it to his farm at No Business, where it housed the family until it burned in the early 1900s.

When the 1910 census was taken, Andrew Watson was lodging with the Millers at their No Business home. He would be killed in New Mexico six years later by Pancho Villa’s bandits while fighting to protect U.S. border settlements during the Mexican Revolution.

Miller still lived at No Business when the 1940 census was taken. His wife, Eliza, had died in 1920, and he had remarried to Elizabeth “Lizzie” Slaven (1903-1978), who was considerably younger than him. She was the daughter of Charley Slaven (1861-1934) and Mary Safrona Roysdon (1872-1957). They were married on May 26, 1922.

Death

At some point after 1940, Miller left No Business — there was a mass exodus going on at the time, as the community’s residents moved out of the river bottoms — and moved to McCreary County, Ky., settling near Bald Knob.

In May 1948, Miller — by then about 91 years old — left his home to look for a horse in the forest. When he did not return, a search was launched. His body was discovered the following day near No Business Creek, 12 miles from his home, by a group of boys who were fishing. A coroner ruled that he had died of natural causes. Following is a newspaper article from the time of his death:

“Franz M. Miller was found dead late Friday afternoon on a lonely mountain path near the Cumberland River and No Business Creek twelve miles from his home in the Bald Knob section, by several boys who were finishing in that vicinity. Coroner Sidney Taylor, Sheriff Coy Perkins and Leo West went to the scene and brought the body out to Stearns, having to carry the body five miles to a highway.

“Relatives stated that Mr. Miller had gone horse hunting Thursday morning and when he did not return that night had started a search for him. His wife and sons who were conducting a search for him were unaware of his death until Saturday noon when they were found searching the isolated hills of the Bald Knob section. The coroner stated that Mr. Miller, who was about 92 years of age, had died from natural causes. He also stated that Mr. Miller had apparently been dead for twenty-four hours.

“Mr. Miller was a pioneer in this section of the country and well known throughout southern Kentucky and Tennessee. He had a wealth of stories of the olden days and the growth of this country and it was always a pleasure for persons to hear him recount these tales.

“The body was removed from Stearns to Oneida on Saturday night, with funeral services taking place Sunday afternoon at two o’clock at the Oak Grove Church, with Rev. Roy Blevins and Rev. Maynard Blevins in charges. Burial was in the Litton Cemetery.”

Miller’s first wife, Eliza Spradlin, was buried at Kidd Cemetery in McCreary County. His second wife, Lizzie Slaven, died in 1978 and was buried at Possum Rock Cemetery.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The WeekenderThursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)