Friday Features: Pennington-Watson Cemetery

Plus: Women's Health Week, and Top of the Middle students in Scott County.

You’re reading Friday Features, a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. This is one of six newsletters we publish each week. You can update your subscription to include as many or as few as you would like to receive. If you need to subscribe, simply enter your email address!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

Sacred Ground: The Pennington-Watson Cemetery

Of the dozens of cemeteries found within the boundaries of the Big South Fork National River & Recreation Area, one of the most mysterious is the Pennington-Watson Cemetery located between Parch Corn Creek and No Business Creek.

This small cemetery, located near the end of the ridge that separates Big Branch from Harvey Branch, is not one of the privately-owned cemeteries within the national park; it’s now owned by the federal government. It is no longer maintained, though it is enclosed by a fence with signage and a fairly well-worn trail leading to it.

Big Branch is located south of No Business Creek. Harvey Branch is located north of Parch Corn Creek. Pennington-Watson Cemetery is accessible from Terry Cemetery Road. A four-wheel-drive dirt road turns down the ridge just before Terry Cemetery, although the final eight-tenths of a mile require traveling on foot.

There are at least 10 graves in this cemetery. Only half of them can be identified. The rest are marked by uninscribed field stones.

All five of the marked stones are Watsons. But the cemetery is the “Pennington-Watson Cemetery.” So how do the Penningtons come into play? That’s part of the mystery.

Part of the Pennington connection is that the two families were connected. Nancy Watson, who died in 1920 and is one of the five verifiable graves at the cemetery, was a Pennington who married into the Watson family.

The Pennington family

It is believed that Lakey Chambers Pennington was buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery when she died in 1901. If so, she would’ve been buried in one of the unidentified graves, almost two decades before the first confirmable burial occurred there.

Lakey Pennington was the daughter of Thomas Chambers (1777-1871) and Catherine Lakey “Katie” Lawson (1792-1838). Both of her parents were the children of Revolutionary War veterans who settled in the Huntsville area in the early 19th century. Thomas Chambers was the son of William Chambers (1750-1840), while Katie Lawson was the daughter of Randolph Lawson.

William Chambers is one of the Revolutionary War veterans of Scott County listed on the plaque outside the old Scott County Courthouse. Randolph Lawson is not, but should be. He moved to present-day Scott County along with two of his brothers, David Lawson and John Lawson, who were Revolutionary War veterans and are listed on the Huntsville plaque. The Chambers family settled on Buffalo Creek, and both Thomas Chambers and Katie Lawson Chambers are buried at Chambers Cemetery there. The Lawson family settled on Paint Rock Creek.

Lakey, who was one of at least 10 Chambers children, married George Washington Pennington, who is believed to have been born about 1824. They married in 1845 and had as many as 13 children.

George Pennington was the son of William Pennington and Susannah Nossman from Whitley County, Ky. He had a brother, Fielding Pennington (1817-1867) who married Lakey’s sister, Sarah Elizabeth Chambers. They settled in the Rockhouse area near Buffalo and are buried at the Cross Cemetery there.

How George and Lakey Chambers Pennington wound up in Big South Fork isn’t clear. Nor is it clear where George Pennington was buried when he died.

At the time of the 1870 census, George and Lakey were living in Scott County’s 5thDistrict with eight of their children: 19-year-old William, George, Martin, James, Elizabeth, Sarazidda, Catharine and two-year-old Mary. William was the fifth-oldest of the Pennington children (behind Daniel, David and Sally), while Mary was the next-to-youngest (Sarah was born two years after that 1870 census). There’s one documented child (Malinda, born around 1843) not accounted for in that 1870 census. (She was listed in the 1860 census, however, and appears to have married by 1865.)

When the 1880 census was taken, George and Lakey were living in the Winfield area with two of their adult children, 30-year-old Sally and 27-year-old Malinda.

The 1890 census is missing, which complicates efforts to trace the family. George Pennington does not show up after the 1880 census. Genealogy reports indicate he may have died in 1884. Lakey Pennington also does not show up after the 1880 census, although the same genealogy reports indicate she may not have died until 1901, one year after the 1900 census was taken.

Relationship to the Penningtons at Pennington-Watson Cemetery

There are two Penningtons purported by some sources (including FindAGrave) to be buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery. One is Lakey Chambers Pennington. The other is Sallie Pennington Slaven (1882-1951).

This Sallie Pennington was the daughter of William Pennington and Patsy Smith — a granddaughter of Lakey Chambers Pennington. She married Elijah Marion Slaven, the son of John Slaven and Elizabeth Smith. He was a deputy sheriff who died of a gunshot wound to the head — determined by a coroner to be self-inflicted — in 1943.

It seems doubtful that Sallie Pennington Slaven is actually buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery. By the time of her death in 1951, it had become uncommon to use field stones to mark graves. Her death certificate at the time of her death states that she was buried in the Slaven Cemetery. When her husband died in 1943, his death certificate stated that he was buried in a family cemetery. Additionally, E.M. and Sallie Slaven did not live in Big South Fork. When the 1840 census was taken, they lived on Buffalo Road east of Oneida. When the 1950 census was taken, Sallie Slaven lived alone on Duncan Road.

The reason for the confusion is Sallie Slaven’s obituary, which stated that she was buried at Pennington Cemetery. The only other Pennington Cemetery in Scott County today is located at Pine Hill; however, she does not have an identifiable headstone there, either.

The location of Elijah and Sallie Pennington Slaven’s graves remains a mystery. If they were buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery, their graves were marked with uninscribed field stones which, again, would seem unlikely in the 1940s and 1950s.

It should be noted that while it’s not clear how Lakey Chambers Pennington wound up in Big South Fork, her son and his family did live in the Big South Fork when the 1880 census was taken. That year, William and Patsy Smith Pennington lived in the BSF with their three oldest children, Lakey, Nancy and Daniel. (Patsy, incidentally, was the daughter of Elijah and Nancy Smith, who lived on Station Camp Creek, where Elijah is buried in a lone grave.)

The only Pennington whose burial can be conclusively proven at Pennington-Watson Cemetery is Nancy Pennington Watson, who died Jan. 1, 1920, at age 43, of tuberculosis. She married James Watson, who was gunned down in Oneida during a pistol dual with Rans Cecil later that same year. He was an employee of the O&W Railroad.

Nancy Pennington Watson was the daughter of William and Patsy Smith Pennington, a granddaughter of Lakey Chambers Pennington.

Is Lakey Chambers Pennington actually buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery? It wouldn’t have been unusual for someone to be buried with only an uninscribed field stone (or an inscribed field stone that has since been rendered illegible by weather and time) to mark their grave in the 1880s or 1890s. And there must be a reason for the Pennington name being affixed to this small cemetery through the years.

The Watson family

The first member of the Watson family — and, thus, the first identifiable grave — buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery was Andrew Watson in 1916.

Andrew Watson was only about 25 when he was killed in combat. His recently-placed flat stone states that he was a member of Wagoner Supply Troop 5thCavalry on the Mexican border during the “Mexican War.” This would be a reference to the Mexican Revolution of 1910 to 1920.

Watson was the son of Elisha Watson and Nancy Slaven. The Watson family lived in the vicinity of Terry Cemetery Road above No Business. When the 1910 census was taken, Andrew Watson was boarding with France and Elizabeth Miller, who lived at the mouth of No Business and operated a general store there.

Andrew Watson enlisted in the U.S. Army around 1910. It was in 1916 that the 5thCavalry was dispatched to the Mexican border to serve in the Pancho Villa Expedition that was being led by Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing. Their assignment was to stop Pancho Villa’s bandits from killing American citizens in the southwestern U.S. Villa had led a raid that resulted in the murders of 17 Americans in the town of Columbus, N.M., in March 1916.

It takes some digging to find the record of Watson’s death. It occurred on Sept. 22, 1916, and is listed on a Punitive Expedition casualty roll. He was one of 46 American soldiers killed or wounded on the Mexican border that year, and one of 12 killed during the Punitive Expedition, which was the original, official name of the Pancho Villa Expedition.

It isn’t clear whether Watson’s body was returned to Scott County for burial or if the stone at Pennington-Watson Cemetery is a cenotaph in his memory.

Elisha Watson, born in 1852, was the son of Hiram Watson and Mary Foster. He married Nancy Slaven in 1883, and they had at least 11 children. Nancy was the daughter of Elisha Slaven and Mary Ann “Polly” Sweet. She was a granddaughter of Richard Harve Slaven, the first settler of No Business Creek.

Among Elisha and Nancy’s 11 children were James, the oldest, who married Nancy Pennington, and Andrew, who was killed in the Mexican conflict.

Nancy Pennington Watson was the next person buried at Pennington-Watson Cemetery when she died of tuberculosis on Jan. 1, 1920. Her husband followed after he was killed in the Oneida dual in August 1920.

Elisha Watson was buried at the cemetery in 1930, and his wife, Nancy Slaven Watson, was buried there in 1945.

The cemetery today

The last burial at Pennington-Watson Cemetery, assuming Sallie Pennington Slaven truly wasn’t buried there in 1951, was Nancy Slaven Watson in 1945. There are at least two — and perhaps as many as four — graves at the cemetery that are unaccounted for. One possibility is that these could be the graves of Hiram Watson and Mary Foster — Elisha Watson’s parents — who died in 1910 and 1915 with burial locations unknown. However, that’s only speculation. (As noted by Tim West in his transcription of Grave Hill Cemetery, there is a funeral home marker in that cemetery for a Hiram Watson, death date unknown, that states he was born in 1824. That is the approximate birth year of this story’s Hiram Watson.)

The Sacred Ground series is part of the Independent Herald’s Scott County Cemetery Project. For even more on Scott County’s cemeteries, see Tim West’s genealogy website.

Ridgeview Behavioral Health Services offers its Mobile Health Clinic at Walmart in Oneida every Monday from 9 a.m. until 3 p.m. (Sponsored content.)

Focus on Health: Empowering wellness and awareness among women

By Sam Voss

Editor’s Note: Focus On Health is a monthly deep-dive into health and medical issues that impact Scott Countians. It is presented by Brennan’s Foot & Ankle Care, Danny’s Drugs and Roark’s Pharmacy.

Every year, Women’s Health Week serves as a vital reminder to prioritize the unique health needs of women. Observed annually in May, typically around Mother’s Day, this week-long initiative encourages women to take charge of their physical, mental, and emotional well-being. In 2025, Women’s Health Week continues to shine a spotlight on preventive care, health equity, and the importance of addressing gender-specific health challenges. This article explores the significance of Women’s Health Week, key areas of focus, and actionable steps women can take to enhance their health.

The Importance of Women’s Health Week

Women’s Health Week, spearheaded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health, aims to raise awareness about the preventable health issues women face and empower them to make informed decisions. Women often juggle multiple roles—caregivers, professionals, and community members—sometimes at the expense of their own health. This dedicated week encourages women to pause, reflect, and prioritize self-care.

The initiative also addresses disparities in healthcare. Women, particularly those from marginalized communities, may face barriers such as limited access to care, socioeconomic challenges, or cultural stigmas. By promoting education and access to resources, Women’s Health Week seeks to bridge these gaps and foster health equity.

Key Focus Areas for 2025

Each year, Women’s Health Week highlights specific health topics relevant to women across all life stages. In 2025, the campaign emphasizes the following areas:

1. Preventive Care and Screenings

Preventive care is the cornerstone of long-term health. Regular screenings, such as mammograms, Pap smears, and bone density tests, can detect issues like breast cancer, cervical cancer, and osteoporosis early, when they are most treatable. Women are encouraged to schedule annual check-ups and stay up-to-date on vaccinations, including those for HPV and influenza.

Cardiovascular health is another critical focus. Heart disease remains the leading cause of death for women in the United States, yet many are unaware of their risk. During Women’s Health Week, women are urged to monitor blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and lifestyle factors like diet and exercise to reduce their risk of heart disease and stroke.

2. Mental Health and Emotional Well-Being

Mental health is inseparable from physical health, yet it often goes unaddressed. Women are more likely than men to experience anxiety, depression, and stress-related disorders, partly due to hormonal fluctuations, caregiving responsibilities, and societal pressures. Women’s Health Week promotes strategies like mindfulness, therapy, and open conversations about mental health to reduce stigma and encourage seeking help.

In 2025, there’s a particular emphasis on postpartum mental health. Postpartum depression affects approximately 1 in 8 women, and awareness campaigns aim to normalize seeking support for new mothers. Community resources, telehealth options, and peer support groups are highlighted as accessible tools for mental wellness.

3. Reproductive and Sexual Health

Reproductive health remains a cornerstone of Women’s Health Week. Education about contraception, family planning, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) empowers women to make choices that align with their goals. For women in their reproductive years, access to prenatal care and safe childbirth practices is critical to reducing maternal mortality rates, which remain a concern, particularly for Black and Indigenous women.

Menopause is another key topic in 2025. As women transition through this phase, they may experience symptoms like hot flashes, mood changes, and increased risk of osteoporosis. Women’s Health Week encourages discussions with healthcare providers about hormone therapy, lifestyle adjustments, and other management strategies.

4. Healthy Aging

With women living longer than ever, healthy aging is a growing focus. Women’s Health Week promotes strength training and weight-bearing exercises to maintain bone health, as well as cognitive activities to support brain function. Nutrition plays a pivotal role, with an emphasis on calcium, vitamin D, and heart-healthy foods to combat age-related conditions.

5. Health Equity and Access

Health disparities persist, particularly for women of color, low-income women, and those in rural areas. Women’s Health Week advocates for policies and programs that expand access to affordable care, including mobile clinics, telehealth services, and community health centers. Culturally competent care is also emphasized to ensure women from diverse backgrounds feel seen and heard.

Taking Action During Women’s Health Week

Women’s Health Week is not just about awareness—it’s about action. Here are practical steps women can take to prioritize their health:

Schedule a Check-Up: Use the week as a prompt to book overdue screenings or wellness visits. Many clinics offer free or low-cost services during this time.

Get Moving: Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, yoga, or cycling. Physical activity boosts mood, heart health, and energy levels.

Nourish Your Body: Focus on a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. Limit processed foods and sugary drinks to support overall wellness.

Prioritize Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep nightly to support mental clarity and physical recovery.

Connect with Others: Build a support network of friends, family, or health professionals. Joining a women’s health group or online community can provide encouragement and resources.

Advocate for Yourself: Don’t hesitate to ask questions during medical appointments or seek second opinions. Being an active participant in your healthcare is empowering.

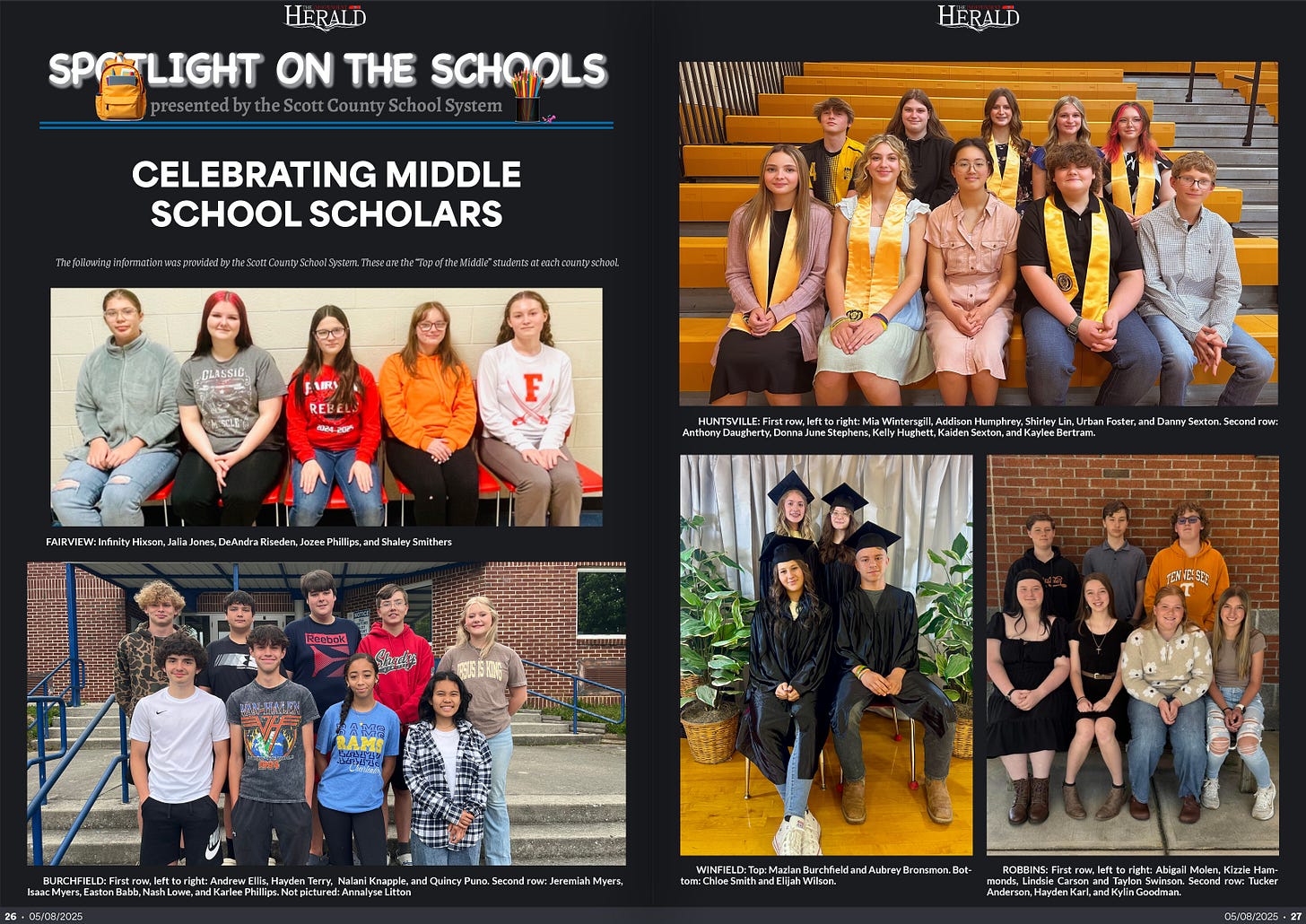

Spotlight on the Schools: The Top of the Middle

Editor’s Note: Spotlight on the Schools is presented by the Scott County School System as a paid partnership with the Independent Herald.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletter will be Varsity this weekend. If you’d like to update your subscription to add or subtract any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t yet subscribed, it’s as simple as adding your email address!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes from the Past (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)