You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

Raiding the Marcum graves in search of Jesse James’ money

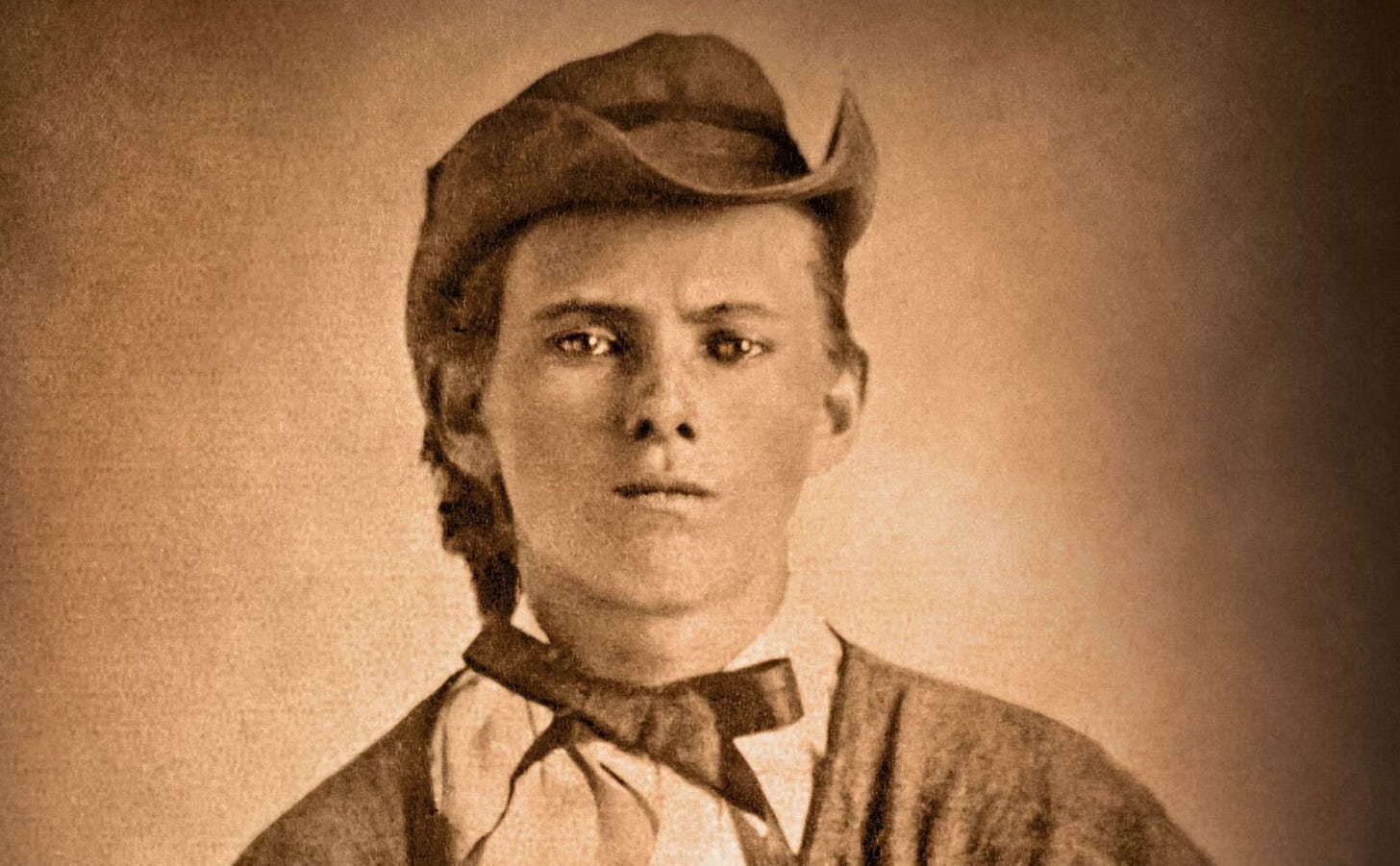

Many rural communities throughout the United States has a Jesse James story — local legends of the infamous Reconstruction-era outlaw slipping in and out of town under the cover of darkness, cloaking himself with an assumed name and the closeness of strangers who didn’t realize his true identity — and Scott County is one of them.

The Cumberland Plateau version of the Jesse James legend goes something like this: Jesse and his brother, Frank, operated a store in Huntsville under assumed identities, stabling their horses with the Marcum family in the Buffalo settlement while they were in town.

Unlike similar legends in other small towns, which can be easily disproven, this one has a bit of bite to it. For starters, both of Scott County’s major historians in the mid 20th century — H. Clay Smith and Esther Sharp Sanderson — wrote at length about the James brothers and their visits to Scott County. Together, their accounts make a compelling case: Jesse and Frank rode into Huntsville shortly after the Civil War, already wanted men but not yet the nationwide celebrities they would eventually become, and boarded with William “Uncle Billy” Sharp — a well-known businessman who owned Huntsville’s first hotel. Their true identities weren’t known at the time, but Sharp later came to believe that the men were Jesse and Frank James, who were by then notorious outlaws.

Like the gospels’ accounts of the birth of Jesus Christ, Smith and Sanderson contain slightly different but very similar versions of Jesse and Frank James’ supposed stay in Huntsville in their respective books, Dusty Bits of the Forgotten Past and County Scott and Its Mountain Folk.

They each also added details that the other didn’t. Smith, for example, tells the story of how Frank James visited a merchant in Hustonville, Ky. many years later and told the man that he and Jesse “had stayed in Huntsville several months under assumed names while ‘scouting’ or ‘laying low’ from officers of the law.

And Sanderson tells the story of the James brothers stabling their horses at the Marcum farm near Buffalo — at a place the locals came to call “Horselot Hollow” as the James legend took root.

In her book, County Scott, Sanderson doesn’t provide the exact identity of the Marcums who assisted Jesse and Frank James, identifying them only as the “Marcums on Buffalo.” The Marcum family lived on Smith Creek near Buffalo during the Civil War, in the area that later came to be known as Marcum Creek, just outside the farm owned today by retired educator Gary Cross. It was in this area that 16-year-old Julia Marcum became famous during the war, when she successfully defended her family’s home from Confederate soldiers who had come to the Marcum farm to arrest and hang her father, Hiram Marcum, for serving as a pilot who guided Union loyalists from East Tennessee north into Kentucky to enlist in the federal army at Camp Dick Robinson. Hiram and his family were eventually driven from their farm by rebel forces in early 1862.

The Marcums referenced by Sanderson would have been George W. Marcum and his wife, Mary Ann Hanks, who continued living at Marcum Creek throughout the Civil War and afterward. They’re both buried at Marcum Cemetery on Marcum Creek. George was Hiram’s brother. They were the sons of Arthur Markham III and Anna Bransgrove, who moved from Virginia to Buffalo in the early 1800s, and may also be buried at the Marcum Cemetery there. Hiram and George had another brother, John Arthur Marcum, who settled in the Pine Creek area of West Oneida and established the Marcum family there.

Like Smith, Sanderson wrote that Jesse James boarded with Sharp in Huntsville and opened a grocery store under the alias Dave Moore. She recounts a story told by Joseph Sharp, the son of “Uncle Billy,” who roomed with James during that time.

“Joseph recalled in later years that Jessie was a congenial, likable person,” she wrote. “He also recalled that he had piercing eyes that seemed to see out of the back of his head. He was a quiet, unassuming person who listened much and said but little. He mixed and mingled with the county folk, and he knew most of them by their first names.”

Suspicion slowly arose. Joseph Sharp remembered afterwards that whenever Dave Moore was out of town, “news of daring robberies by the James Brothers and their band would be narrated.”

Then there was the case of a Buffalo man named Mitt Adkins. He was frequently seen with Dave Moore. And then there were reports in the newspapers that a Clell Miller had been killed during a daring bank robbery by the James Gang in Missouri. Adkins was never again seen in Scott County, and Sanderson wrote that local folks came to assume that Clell Miller was actually Mitt Adkins.

The Mitt Adkins referenced by Sanderson may have been Milton Adkins, son of Henry and Elizabeth Adkins. He was born in 1841, and appears in the 1850 census as 9-year-old “Melton Adkins” and in the 1860 census as 19-year-old “Millon Acktins.” He doesn’t appear in census records after 1860. His parents moved to Campbell County, and appear to have died between 1880 and 1900. (Mitt Adkins almost certainly was not Clell Miller; more on that story in next week’s edition of Echoes in Time.)

By now, suspicions were rampant in Scott County that Dave Moore — the quiet, mysterious storekeeper from Huntsville — was actually the outlaw Jesse James. When James was killed in 1882, Joseph Sharp told Sanderson, his father (Uncle Billy) looked at a picture of James in his casket that appeared in a newspaper and said, “Dave Moore will never visit his store in Huntsville again.”

There were other suspicions, too. In the Buffalo community, where the Marcum family had kept the James brothers’ horses secured during their time in Scott County, George Marcum and his wife “seemed to always have money regardless of how hard the times were,” Sanderson wrote. “It is doubtful whether the Marcums knew the actual identity of the outlaws, but inasmuch as they had to hide their loot, some of it could possibly have been found; while on the other hand, they could have been paid ‘liberally’ for their kindness and services.”

Sanderson wrote that a descendant of George and Mary Ann told that George gave each of his children $600 in gold before he died in 1891, “and where it came from they never knew.”

It was in 1887 that Mary Ann Hanks Marcum died. And the legend grew. In those days, it was customary to “sit up” with the dead. These were the days before mortuaries or funeral homes, and while the custom of “sitting up with the dead” has been romanticized in popular culture, the cold, hard truth of the practice was that it was to protect the body from rodents until it could be properly buried. In time, however, Appalachian people came to view “sitting up with the dead” as a way to honor the deceased by not leaving their body alone. But a rumor spread: in the dark room where Mary Ann’s body lay, someone tiptoed into the room just before dawn and placed something inside the wooden casket. “Could this have been some of the hoarded gold of the James Brothers?” Sanderson speculated.

Many years later, the Marcum graves were looted by grave-robbers who decided to find out for themselves if money had actually been buried with Mary Ann when she died. According to Sanderson: “Under the cover of darkness, (three men) slipped to the cemetery and dug up the remains of Mrs. Marcum. They did not find the expected pot of gold, but they did encounter the unexpected law who lodged them in the Huntsville jail where one died immediately after, presumably from poisonous fumes from the grave.”

It would have been quite ironic if the Marcums and the James brothers actually formed an alliance. Unlike the version of Jesse James that has been romanticized by Hollywood, the real Jesse James was a staunch supporter of the Confederate cause who resorted in violence after the war as a way to fight back against Republicans and Reconstruction efforts in his native Missouri that sometimes treated the former rebels harshly. In Scott County, though, the Marcums were staunch supporters of the Union cause. George’s nephew, also named George Marcum, had been gunned down by Confederates on the family’s Smith Creek farm, and his brother’s family (Hiram) was driven away from the family home because of their support for the Union.

However, in 1867 and 1868, when Jesse James was supposedly in Huntsville, his identity was unknown to people like Uncle Billy Sharp and George Marcum. He was simply Dave Moore, the unassuming storekeeper, who needed somewhere to stable his horses.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The Weekender Thursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)