You’re reading Friday Features, a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. If you’d like to adjust your subscription to include (or exclude) any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t subscribed, please consider doing so!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

A family feud

Two bodies in the ground at Chimney Rocks, both murdered. One an orphan girl nobody wanted. The other a young father shot in the back on his birthday.

Between them: six months, a wedding, and yet another tragedy in the Station Camp community along the Big South Fork River.

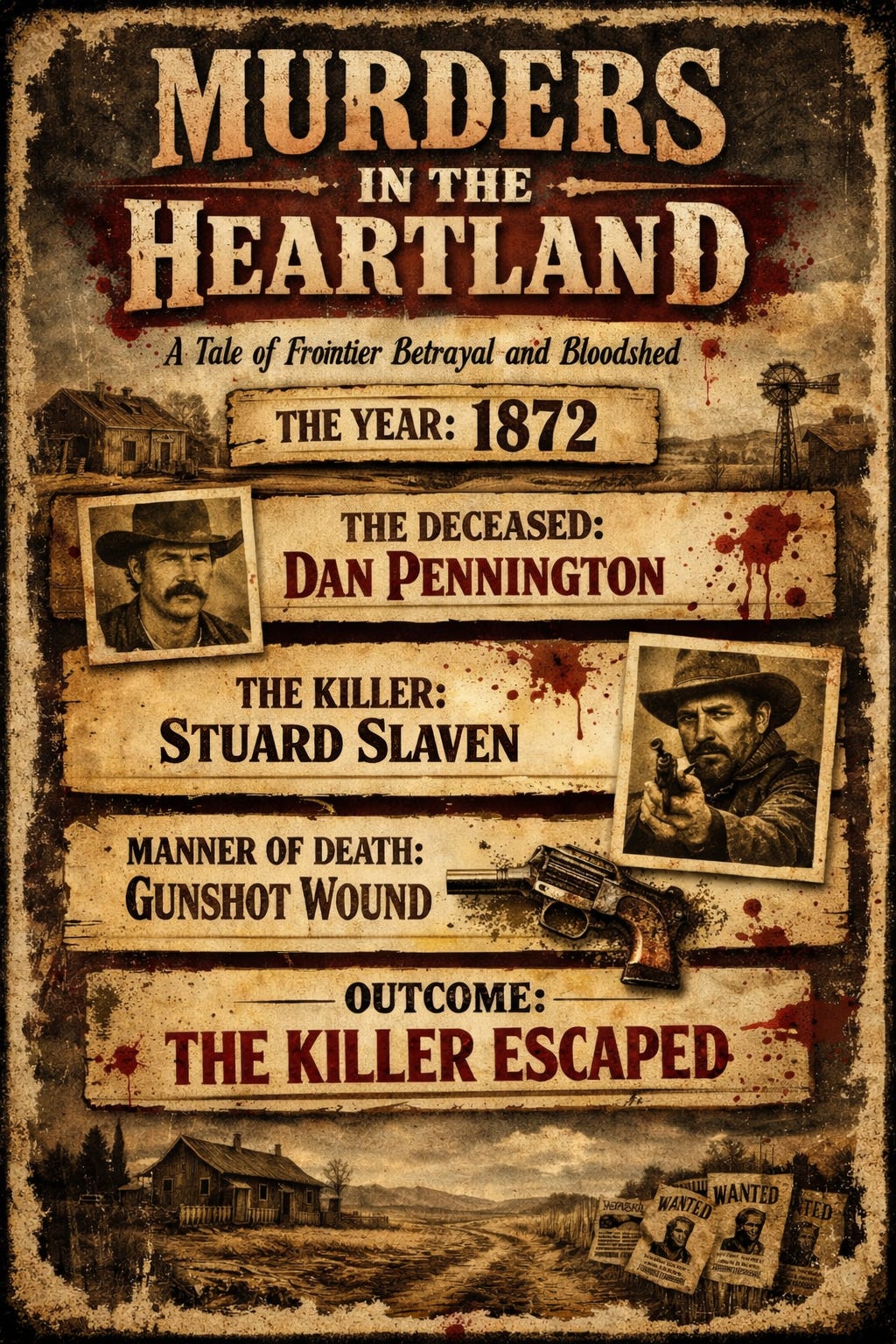

Dan Pennington turned twenty-nine on July 9, 1872. By the next day, he was dead – three bullets in his back, alone in the woods above Station Camp.

The killing had been building for months, maybe from the moment he married Susan Slaven. She was frontier royalty: granddaughter of the first white settler in the Big South Fork, daughter of Absalom and Betty Wood Slaven. Dan was a widower with two small children, his first wife Peggy dead less than a year.

The match might have seemed practical, but it wasn’t.

Susan’s brothers despised him.

The eruption came on Dan’s birthday. Elias Meshack “Shack” Slaven – one of those protective brothers – showed up at Dan’s house with a rifle. The Nashville papers called it a “personal difficulty,” which was one way to describe resting a gun on a fence and taking aim at your brother-in-law. Shack fired and missed. Dan shot back with a pistol, hitting Shack in the shoulder. Shack ran.

Dan ran too. He knew what was coming.

He went into the forest. Someone followed him there. Someone came up behind him and fired twice, maybe three times. Dan collapsed. He died the next day, July 10, remaining conscious long enough to name his killer.

They buried him at Chimney Rocks, the same lonely spot where they’d put Angeline Moore six months earlier – a mutilated orphan girl found on Huckleberry Ridge like discarded refuse.

Two murder victims. Two graves. No justice for either.

***

Dan told his wife – pregnant with their first child together – that one of her brothers had killed him. Not Shack, the one he’d shot. Another one. Stuard. Dan said he saw Stuard running from the trees after the gunshots. Years later, the Scott County Call reported that Stuard had confessed to acquaintances before disappearing: “Don’t blame Shack. I killed him.”

A grand jury indicted Stuard Slaven for murder.

Then authorities arrested Anderson Lewallen instead.

The Lewallen arrest makes no sense on paper. Anderson was the son of John Lewallen, Scott County’s first sheriff. He was respected, and had served as a justice of the peace in the 1860s. In fact, he’d officiated Shack Slaven’s wedding back in 1866. He was in Scott County when Dan was killed, stayed a full year after. Then he went to Texas to join his father, the ex-sheriff who had left Tennessee after marrying his second wife.

In 1873, Anderson came back to Scott County for a visit with his brother-in-law, Elihu McDonald. They arrested him for helping murder Dan Pennington. Despite Stuard Slaven already being under indictment. Despite Dan’s deathbed accusation. Despite everything.

Was it politics? Some old grudge? Wrong place, wrong time? Wrong last name?

At trial, the defense put Susan Slaven Pennington on the stand. The widow repeated what her dying husband had told her: Stuard had pulled the trigger. The jury deliberated and acquitted. The Scott County Call later wrote: “The prosecution must be satisfied, after hearing the evidence, that Lewallen was wrongfully accused.”

Anderson went back to Texas and never returned.

***

Stuard Slaven never stood trial. He fled west, died in Fresno in 1911. Shack vanished to Arkansas with his wife Celia and died there in 1922. Neither brother ever came back to Scott County.

Susan stayed. She remarried to William Owens, who ran a grist mill on Station Camp Creek and owned one of the biggest farms in the valley. They had many children together.

Then smallpox came.

Samantha died at 13 in 1888. Lawrence died at 10 in 1892. Sarah died as a toddler. James died before his first birthday. Electa died in 1896. George died in 1900.

William himself died in 1903, and was buried in a row with his children on a hill overlooking the farm – graves now swallowed by forest in the Big South Fork National River & Recreation Area, a horse trail wandering by them but most riders unaware they’re tucked away just out of sight.

Susan left Station Camp after William died. She moved to Mt. Pisgah, Kentucky, just across the state line from Pickett State Forest, where she lived until 1935, when she died at 82. She was a woman who buried two husbands, nearly every one of her children, and two brothers’ reputations.

The hills don’t tend to forget. And at Chimney Rocks, two graves kept their silence.

(Footnote: Dan Pennington’s children were William, who moved to California, and Almeda Pennington West, who remained in Scott County. Susan Pennington Owens had two surviving children, Cordelia Owens Paul and Baily Owens, who were later buried at O’Possum Rock Cemetery in the Black Oak community when they died in 1970 and 1975, respectively. No one was ever convicted of Dan Pennington’s murder.)

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletter will be The Daybreaker bright and early Monday morning. If you’d like to update your subscription to add or subtract any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t yet subscribed, it’s as simple as adding your email address!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes from the Past (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)