Sacred Ground: Hembree Cemetery

The Hembree family was one of the first to settle Smokey Creek, beginning with Meshack Hembree

You’re reading Friday Features … on Saturday (sorry for the delay!). Friday Features is a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. If you’d like to adjust your subscription to include (or exclude) any of our newsletters, please do so here. If you haven’t subscribed, please consider doing so!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

Sacred Ground: Hembree Cemetery

The Smokey Creek valley — a peaceful and fertile bottomland deep in the Cumberland Mountains — is Lowe country, dating back to when Mikel “Grand Mikey” Low settled in the valley and became perhaps the first white settler in what would eventually become Scott County, Tennessee.

But Smokey Creek is also Hembree country. In fact, the Shack’s Creek area towards the head of Smokey Creek was once called Hembree. There was a post office there and even a school at one point. Today, the only store that remains open in these old coal mining communities along the former Tennessee Railroad is Hembree’s Grocery at Smokey Junction, the old whistle stop located where Smokey Creek empties into New River.

The Hembree Cemetery is located in the heart of the settlement that once bore the name of the area’s most prominent family. It dates back to 1870 and consists of nearly five dozen burials.

The Hembree family

The Hembree family of Smokey Creek dates back to Meshack Hembree. (Remember, the stream that flows into Smokey Creek is named Shack’s Creek — for Meshack.)

The Hembree family originally settled in Georgia after migrating from England and landing at Savannah in 1737. From there, the family put down roots in South Carolina. The surname was originally spelled Armory but was changed to Hembree by John Hembree (1744-1808). His mother was Mary Moore, whose family was among the most affluent in South Carolina colony during the 18th century. Both her grandfather and her uncle served as provincial governors during the colonial era, and the Moore family was one of the most prominent families in the South Carolina slave trade.

John Hembree Jr. — John Amory Hembree’s son — was one of the many adventurous pioneers who began leaving the plantation country of Virginia and the Carolinas and moving west through the Cumberland Gap after the Revolutionary War ended. He moved his family from South Carolina and settled in eastern Kentucky near present-day Barbourville.

From there, most of John Hembree Jr.’s children moved to present-day Scott County — including Meshack Hembree, who settled on Smokey Creek.

Meshack had a brother, W.B. Hembree, who is buried at Huntsville Cemetery. Another brother, James Hembree, is also buried at Huntsville. Yet another brother, Robert Hembree, also moved to present-day Scott County, but it isn’t clear where he was buried. Finally, the Hembree brothers had a sister who married in Scott County, though she may have returned to Kentucky after the death of her husband.

The continuing story of Meshack Hembree

The date of Meshack Hembree’s arrival in present-day Scott County isn’t known with certainty. He was living at Smokey Creek when the 1860 census was taken, but for reasons unknown does not show up in census records prior to 1860. His brother, Robert Hembree, married in Anderson County in 1839, which probably indicates that the Hembree siblings had moved to the area prior to 1840.

Meshack Hembree had married his first wife, Martha “Kissiah” Carroll, by the time their first child was born in 1833. The Carroll family also lived at Smokey Creek. Martha’s parents were John “Drewry” Carroll and Nancy King. As you may recall from the story of the Lowe Cemetery at Smokey Creek, Drewry Carroll and his family arrived on the scene at about the same time as Mikel Low. The Carroll family moved to Smokey Creek from North Carolina, while the Hembrees moved to Smokey Creek from Kentucky. This makes it seem likely that Meshack Hembree met Kissiah Carroll after both had made the move to Smokey Creek. (Meshack had a sister, Martha Patsy Hembree, who married Kissiah’s brother, Alexander Carroll.) This helps nail down the timeline of their arrival as being well before 1840.

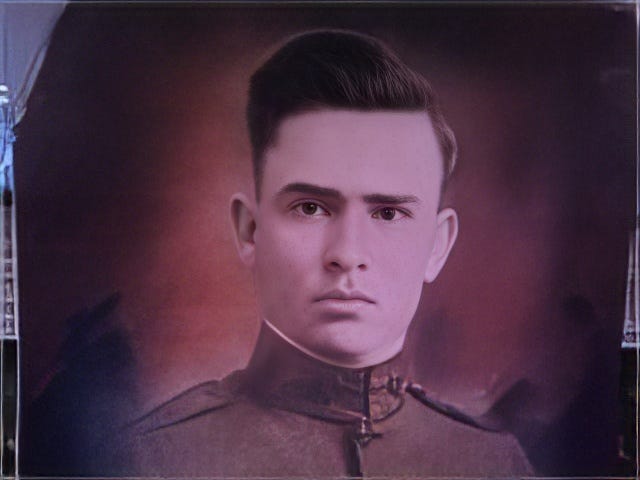

Hembree served in the Union army during the Civil War. He enlisted at Somerset, Ky. in December 1861 and was assigned to the 2nd Regiment of the East Tennessee Volunteers. He suffered a non-combat injury in 1862 and was apparently disabled, according to a request for an invalid’s pension that he filed after the war.

Hembree’s son, William Alexander “Bill” Hembree, also served in the Union army during the war. He was a captain in the Scott County Home Guard and was said to have been wounded on 13 different occasions during the war.

According to local historian David Jeffers, there was a cave on Smokey Creek to which Bill Hembree would return to recover after being wounded. There, his mother and wife nursed him back to health.

At one point late in the war, Bill Hembree was severely beaten by Confederate guerrillas at New River. The guerrillas attempted to force Hembree’s horse to trample him. When the horse refused, the soldiers shot the horse dead and left Hembree to die — although he was able to survive.

After the war, Bill Hembree became a noted leader in the Smokey Creek community. He ran a grocery store and a boarding house, and donated the property where the Hembree School was established. He also served as the first postmaster at the Hembree Post Office. In 2023, Scott County Commission named a bridge on Smokey Creek Road in Bill Hembree’s honor.

Bill Hembree was just one of at least 12 children fathered by Meshack Hembree, who may have fathered children with three different women. Other children are believed to have included Nancy Louise, Rebecca, Sarah, Ezekiel, Jennie, Jemima, Elizabeth, Harmon, Mary Jane, Kissie and James Martin. There may have been others.

Meshack Hembree and Kissiah Carroll divorced in 1873, after she accused him of adultery. It is written that she returned to using her maiden name after the divorce. However, her headstone at Hembree Cemetery reads “Kissiah Carroll Hembree” and denotes that she was the wife of Meshack Hembree.

Meshack subsequently married Ibey Smith, the woman with whom he was accused of having an affair. She died in 1884 and is also believed to have been buried at Hembree Cemetery.

When Meshack Hembree died in 1885, he had three minor children who were orphaned. They were Mary Jane, Kissie and James Martin. Their older brother, Bill Hembree, was appointed their guardian.

The cemetery begins

Bill Hembree married Emily Shoopman, who was a granddaughter of Mikel Low, in the late 1850s. Her mother, Elizabeth Low, married John Shoopman Jr. The Shoopmans were another early families of Smokey Creek, along with the Lowes and the Carrolls and the Hembrees.

On June 1, 1870, one of Bill and Emily’s daughters, four-month-old Rebecca Hembree, died. She was the first person buried at Hembree Cemetery, which is located on a small knoll above Meshack’s Creek (Shack’s Creek).

Rebecca was the only burial on the knoll until Kissiah Carroll Hembree died in March 1879, followed by Meshack’s second wife, Ibey Smith Hembree, in 1884. It should be noted that while family historians believe Ibey Hembree was buried at the cemetery there is no stone to identify her grave.

Meshack Hembree was the fourth person buried at the cemetery when he died in 1885.

The Lowe family

As could be expected, the Hembree and Lowe families were closely connected, beginning with the marriage of Meshack Hembree’s son, Bill, to the granddaughter of Mikel Low.

Meshack’s daughter, Jemima, married a grandson of Mikel Low — Phillip Low Jr. And one of their sons — Alexander “Alex” Lowe — married one of the daughters of Bill and Emily Hembree — Luvirna. Alex and Luvirna were second cousins, which was not at all unusual during the early settlement era when rural communities were isolated from the rest of the world.

Alex Lowe’s kid sister, one-year-old Almira Low, was buried at Hembree Cemetery in March 1886. She was the fifth person buried there. Her mother, Jemima Hembree Low, was later buried at the cemetery in 1906. Her father, Phillip Low Jr., died later and was buried near Caryville.

The story of Alex and Luvirna Hembree Lowe was a tragic one. They lost many children at young ages, beginning with their one-year-old son, Foister Lowe, who was buried at Hembree Cemetery in March 1895. They had a baby girl, Magie Bell, buried at the cemetery in October 1900. Other children buried at the cemetery included 15-year-old Marion in 1906, 16-year-old Franklin in 1911, 11-year-old Linzy in 1915, 13-year-old Elbert in 1919, and 14-year-old Virginia in 1928. Even in an era when it was not uncommon for people to die young, Alex and Luvirna had an exceptional number of children who died in their teens. They also had another newborn daughter, Celia, buried at the cemetery in 1911.

Alex and Luvirna were later buried at the cemetery in the 1940s. Two of their children who survived to adulthood — Hiter and Nelson — were buried at the cemetery in 1949 and 1978, respectively.

Meanwhile, another of Bill Hembree’s daughters, Louisa, married Columbus Lowe. She died in 1902 at age 28 and was buried at Hembree Cemetery. Her husband remarried and moved to the Robbins area.

Other early burials

Other early burials at Hembree Cemetery included Hannah Seiber and Jemima Hall, both in 1893.

Hannah was the daughter of Bill and Emily Shoopman Hemree. She was just 25 when she died. She married Mike Seiber, who was not buried at the cemetery.

Jemima was Hannah’s sister. She married Milton Hall, and was just 27 when she died eight months after her sister. She had four children under the age of 10 when she died. Milton and the children left Smokey Creek and moved to the northwestern U.S.

Remember that Hannah Seiber and Jemima Hall were the sisters of Louisa Hembree Lowe. Three sisters, all in their 20s, died and were buried at the cemetery during a 10-year span.

Other early burials included Parzida Byrd in 1904, Clifford Hembree in 1906 and Johnie Hembree in 1910.

Parzida was the daughter of Phillip Low Jr. and Jemima Hembree. She married Phillip Byrd and was 25 when she died in 1904. Clifford Hembree was the nine-month-old son of John Hembree and Minnie Lowe. John was the son of Bill Hembree and Emily Shoopman. He married the daughter of John Low and Nancy “Renee” Adkins.

Johnie Hembree was the three-year-old son of Alvis and Etta Hembree. Alvis was another grandchild of Bill Hembree and Emily Shoopman. Johnie died of diphtheria, which was an infection of the throat. He had a newborn brother, Egbert Hembree, buried at the cemetery in 1912, and a 19-year-old brother, Foster Hembree, buried there in 1918.

In 1911, Nelson Low and Harrison Low were buried at the cemetery within eight days of one another. They were the sons of Phillip Low Jr. and Jemima Hembree. Harrison shot Nelson on Nov. 7, 1911 and was killed himself a week later. History doesn’t tell us who killed Harrison; only that he was killed by a shotgun wound. He was 30 at the time of his death; his brother was 25.

Several other members of the Hembree family were buried at the cemetery in the 1910s. One of them is unknown, due to the stone being broken. The death occurred in 1916 and is believed to be an adult child of Bill Hembree and Emily Shoopman. Dora Hembree, the seven-year-old daughter of John and Minnie Lowe Hembree, was buried at the cemetery in 1918. And John was buried there when he died the following day.

Nineteen-year-old Foster Hembree, seven-year-old Dora Hembree, and 35-year-old John Hembree all died within 48 hours of one another in October 1918. Although history doesn’t tell us what they died of, the timing would suggest that they were victims of the Spanish flu pandemic that was raging in this part of the world in 1918.

The Daugherty family

Harry Daugherty was buried at Hembree Cemetery in 1924. He was the five-year-old son of Fisher Daugherty and Louvernia Bunch. Fisher had died two years earlier when he was killed — along with his father and his brother — during a dispute at Fork Mountain in Morgan County.

Louvernia, who was a granddaughter of Phillip Low and Jemima Hembree, had returned to Smokey Creek after her husband’s murder. She remarried to Caleb “Cas” Carroll, the son of Huston Carroll and Angeline Mason. She was later buried in Morgan County.

There is another Louverna Daugherty buried at Hembree Cemetery in 1940. She was the daughter of Hiram and Martha Daugherty. Hiram Daugherty was also buried at the cemetery in 1959. Hiram and Harry Daugherty were not closely related.

The cemetery today

The last burial at Hembree Cemetery was Linda Massengale Lowe in 2018. She was the 96-year-old widow of Nelson Lowe, a son of Alex Lowe and Luvirna Hembree who was buried at the cemetery in 1978. Linda’s parents were John “Frank” Massengale and Mary Jane Bunch, who are buried at nearby Lowe Cemetery. She had several newborn children buried at the cemetery in the 1940s and 19650s: Jenefer Louise in 1941, Johnie Waine in 1953, and Roger Dean in 1951. An adult son, Billy Wade Lowe, was buried at the cemetery in 2013. His wife, Joyce Ann Harness, was buried at the cemetery in 2017.

Those three — Linda Lowe, her son, and her daughter-in-law — are the only people who have been buried at Hembree Cemetery since 1990. Burials at the cemetery largely ceased in the 1970s. However, Wesley Hembree was buried there in 1988 and Minerva Lowe was buried there in 1990. Wesley was the son of John Hembree and Minnie Lowe. His wife, Annie Gibson, was buried at the cemetery when she died young in 1937. Minerva — “Nerva,” as she was known — was the wife of Hiter Lowe. Hiter was one of the few surviving children of Alex Lowe and Luvirna Hembree, who was buried at the cemetery in 1949.

For a complete transcription of the Hembree Cemetery, see Tim West’s genealogy website.

Sacred Ground is an ongoing series of the Independent Herald. For more, see the Scott County Cemeteries page on the Encyclopedia of Scott County.