You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

Civil War days: The strategic importance of Camp Dick Robinson

By the summer of 1861, sides had been chosen in America’s greatest internal conflict. Beginning with South Carolina on Dec. 20, 1860 and ending with Tennessee on June 8, 1861, eleven Southern states broke away from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America, sparking the Civil War. And once Tennessee had become the final state to secede, thousands of men from across East Tennessee picked up their guns and headed north into Kentucky to join the fight. Many of these men — including dozens from Scott County — would train at Camp Dick Robinson.

Understanding the battle lines

When Tennessee’s first secession referendum was held in February 1861, the state’s voters rejected a call to join the Confederacy. But Gov. Isham Harris, the fiercely anti-Lincoln Democrat refused to take “no” for an answer, and when the Battle of Fort Sumter occurred and Lincoln called for all states — including Tennessee — to furnish troops in order to squash the Southern rebellion, the mood shifted.

Tennessee’s second secession referendum, on June 8, 1861, saw the state’s voters give a nod of approval to leaving the Union. But they did so despite objections in East Tennessee. The entire eastern third of the state was opposed to secession, none moreso than Scott County. Here, the vote was 541-19 in favor of remaining loyal to the Union — the most lopsided margin of any county in the state.

It’s often said that Scott Countians didn’t want a part in the fight; that they simply wanted to be left alone. That’s not entirely true. Scott Countians did not remain neutral in the fight. Hundreds of them joined the federal army, and a few dozen more joined the Confederate army. Paul Roy, who became Scott County’s preeminent Civil War historian when he compiled Scott County in the Civil War (which is available for purchase through the Scott County Historical Society), counted more than 600 Scott Countians who fought for the Union.

The role of Camp Dick Robinson

Eventually, some Union regiments would be raised in Tennessee — including right here in Scott County, where a Chattanooga man named William Clift formed the 7th Tennessee Infantry. But initially, any man from East Tennessee wanting to fight for the Union — and there were a lot of them — had to slip north into Kentucky to do so. Some Scott Countians served as pilots to help these pilgriming recruits find their way through the rugged terrain of the Cumberland Mountains and into the Bluegrass State. One of them who did so was Hiram Marcum of Buffalo, and it cost him greatly.

Kentucky had been viewed as neutral as the secession crisis unfolded in 1860 and 1861. However, local leaders obtained 700 muskets from U.S. Navy Lt. William “Bull” Nelson and distributed them to Home Guard troops who were loyal to the Union. The Home Guard countered the State Guard, which was a loosely organized group of Kentuckians that favored secession. Slowly, sides were being chosen in Kentucky, as well.

Garrard County Judge Allen A. Burton traveled to Washington, D.C. to urge President Abraham Lincoln to organize Union loyalists from Kentucky into regiments. There, he encountered Lt. Nelson and recommended him for the mission. Nelson met with U.S. Sen. Andrew Johnson from Tennessee — the man who had traveled to Huntsville and helped convince Scott Countians to vote against secession — and Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Together, the three men began to formulate a plan of support for loyalists in East Tennessee.

Throughout the early days of the war, Sen. Johnson and his counterpart, U.S. Rep. Horace Maynard, urged Lincoln to help the Union loyalists in East Tennessee — including those in Scott County, aware that their loyalty to the Union would cause them to be targeted by the rebels. And by July 1, 1861, plans were being formulated to do just that.

It was on that date that Lt. Nelson was detached from the Navy with instructions to organize a force of 10,000 troops. Their purpose would be to march into East Tennessee and root out the Confederate faction here. In order to raise the army, Nelson needed a training facility. He spoke with Union leaders in southeastern Kentucky at Lancaster and Crab Orchard, and ultimately chose an old inn at Bryant Springs as his headquarters. He had an agreement to raise 30 companies of infantry and five companies of cavalry.

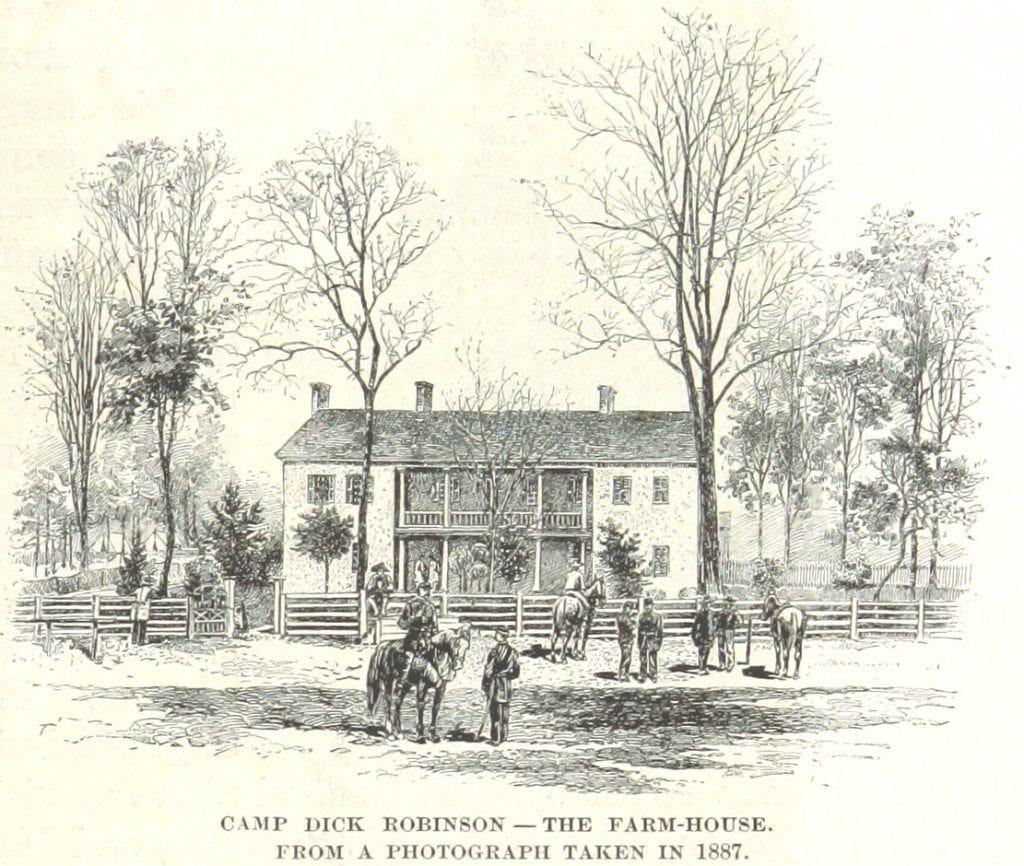

Lt. Nelson ultimately determined that a 425-acre farm owned by Richard M. “Dick” Robinson at Hoskins Crossroads — seven miles north of Lancaster — was a better site for a training base. He convinced Robinson to lease the farm to him. The main house was a tavern with a storehouse. There was also a blacksmith shop, a barn, mule shed, and several other outbuildings. The farm extended half a mile along Danville Pike, and another half a mile along Lancaster Pike.

The first company arrived at Camp Dick Robinson on July 20, 1861, followed closely by a second company on July 24, 1861. Camp Dick Robinson became the first federal military base south of the Ohio River.

On Aug. 5, 1861, Union loyalists in Kentucky won a majority of seats in the state’s House of Representatives (76 to 24) and Senate (27 to 11). That cemented Kentucky’s stance as a Union state. And it led to renewed calls for recruits to encamp at Camp Dick Robinson. The base was officially designated on Aug. 10, 1861.

Kentucky Gov. Beriah Magoffin sent a request to Lincoln, urging the president to remove federal troops from Camp Dick Robinson. Lincoln declined, saying the base had been “established at the request of many Kentuckians,” and that the men encamped there was an “indigenous force.”

Raising the army

By the end of August 1861, Nelson had 3,200 troops, 7,000 arms and six pieces of artillery at Camp Dick Robinson. The 1st Tennessee Infantry and 2nd Tennessee Infantry, led by Col. Robert K. Byrd and Col. James P.T. Carter, respectively, each had 1,000 men.

Many of the new recruits were Union loyalists from East Tennessee who slipped northward into Kentucky to join the federal army. Of the men from Scott County who enlisted at Camp Dick Robinson, many were assigned to the 2nd Tennessee Infantry, which would later be involved in the fateful Battle of Rogersville in Hawkins County, Tenn.

Among those from Scott County who trained at Camp Dick Robinson were Brimstone brothers Hamilton Griffith and Fielding Griffith. In October 1861, a woman visited the base selling pies — which were apparently poisoned. Fortunately, Hamilton Griffith had fed part of his pie to a dog, and realized something was wrong when the dog immediately became sick and died. His brother was not as fortunate. Fielding Griffith ate his pie, and became ill and died soon thereafter. He was the first known casualty of the war from Scott County.

The Confederates respond

Confederate Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, who was in command of Rebel forces in East Tennessee, learned that Nelson was adding as many as 400 to 500 men per day to his ranks at Camp Dick Robinson. He began formulating a plan to stop the raising of the army in southeastern Kentucky.

To the north, concerns mounted that Zollicoffer would help lead a two-pronged advance on Kentucky from Knoxville and Nashville in an attempt to seize Frankford and force the state into the Confederacy. U.S. Sen. Garrett Davis of Kentucky said that Camp Dick Robinson “must not be removed, even if it be the cause of civil war.” Indiana Gov. Oliver P. Morton added, “if we lose Kentucky now, God help us.”

On Sept. 3, 1861, Confederate forces moved into western Kentucky and occupied the town of Columbus. The Kentucky General Assembly responded by requesting Gov. Magoffin to “call out the military force of the state to expel and drive out the invaders.”

Nelson was relieved of his command at Camp Dick Robinson and ordered to raise a brigade to stop the Confederate advance toward Lexington. He was replaced by Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas, who assumed command at Camp Dick Robinson on Sept. 15, 1861.

Four days later, Zollicoffer’s advancing forces seized the town of Barbourville, making the town a base of operations for its march on Lexington and Richmond. There were as many as 8,000 Confederate soldiers at Barbourville, leading Lincoln to issue a memorandum stating that Union forces seize the railroad that connected Virginia and Tennessee near the Cumberland Gap.

On Oct. 21, 1861, Union forces defeated Confederates at the Battle of Camp Wildcat. From there, Thomas pursued Zollicoffer near Somerset in November 1861. His initial army was joined by new recruits who had trained at Camp Dick Robinson — including some from Scott County — and the Battle of Mill Springs was fought on Jan. 19, 1862. It was there that Zollicoffer was killed, and the outlook of the war in East Tennessee changed completely.

With Zollicoffer dead and his rebel forces in tatters, the Army of the Ohio was able to march into Middle Tennessee and occupy Nashville in February 1862. Tennessee Gov. Isham Harris was forced to flee the state capitol. In Scott County, the occupying Confederate force was in disarray, which gave rise to a period of lawlessness that persisted through 1863.

Best laid plans

The primary mission that the men of Camp Dick Robinson were training for — an invasion of East Tennessee to free Scott County and the rest of the region — never happened.

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who would later rise to fame by leading the Union army’s backbreaking march through Georgia, became concerned that Confederate forces amassed at the Cumberland Gap were too many. East Tennessee loyalists had undertaken preemptive missions to destroy railroad bridges throughout the region in an attempt to hinder the Confederate army’s movement. When the Union backed off its plans to invade, loyalists in East Tennessee were left to the mercy of enraged Confederates — including Gov. Harris, before he was forced out of Tennessee by the Union takeover of Nashville. It wasn’t until September 1863 that Union soldiers, under the command of Gen. Ambrose Burnside, finally marched into East Tennessee — passing through Scott County in the process — and seized control of Knoxville from the Confederacy.

The downfall of Camp Dick Robinson

In August 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smart entered Kentucky with 12,000 forces and seized Camp Dick Robinson. Later, Confederate Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg ordered a new Confederate camp to be established on Dick Robinson’s farm. It was called Camp Breckinridge.

Confederate control was short-lived. The Army of the Ohio defeated Bragg’s army at the Battle of Perryville, forcing Bragg to withdraw from Kentucky on Oct. 13, 1862. The rebel soldiers abandoned stores at Camp Dick Robinson, which were seized by the Union army.

On Aug. 21, 1863, as Gen. Burnside’s 12,000-man-strong army marched southward towards Scott County, they paused at Camp Dick Robinson to reinter the remains of Lt. Bull Nelson — who had been killed in a dispute with a fellow officer — behind the original headquarters home. From there, Burnside’s men entered Scott County at Winfield and No Business, the two columns joining at New River and traveling up Brimstone Creek before crossing the mountains and marching on Knoxville.

The federal government’s lease of Dick Robinson’s farm ended on June 1, 1865. Robinson sued the government for the money owed him for use of his home and land. He died bankrupt in June 1869, having never been paid the money owed him. The money was eventually paid to his widow, Margaret P. Robinson, following action by Congress.

Margaret Robinson sold part of the farm in 1884, and Lynn Hudson sold the home and 335 acres in 1895. In 1905, the final parcel of land associated with Camp Dick Robinson was sold.

In 1990, the National Register of Historic Places added the Robinson house to the listings for Garrard County. However, its owners at the time added a brick facade that caused the building to be removed from the register. The original appearance of the farm was also altered when U.S. Highway 27 was built in the 1920s.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The Weekender Thursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)

Thank you for a very interesting article. I have never read such a detailed summary of the activities in Scott Co, and the rest of east TN, during this period. I had thought there was a father-son Griffith pair during Revolutionary War time with the same names mentioned in this article about Civil War times, which are listed as being brothers. Who was their father? I'm wondering how closely I'm related to them.