Scott County native prepares for publication of first novel

Plus: A colorful smorgasbord awaits the northern plateau, and the Sacred Ground series visits A.J. Robbins Cemetery

You’re reading Friday Features, a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. If you’d like to adjust your subscription to include (or exclude) any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t subscribed, please consider doing so!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

Scott County native prepares for publication of first book

Katie Bond Swafford, a 2016 graduate of Scott High School, is preparing to publish her debut novel, Genesis of the Fall, on Nov. 1.

Swafford is the daughter of Jeremy and Ginger Bond, and is proud to call Scott county her home.

A wife, mother, and soon-to-be published author, Swafford has always had a passion for storytelling. That passion showed itself early — so much so that she often got in trouble in the 4th grade for reading library books during math class. By junior year, her talent was recognized on a larger scale when she placed in Category 2 in a statewide writing assessment.

“My main inspiration was to give my kids something they could be proud of their mommy for,” she said. “I also hope to inspire those who love to read and write to shoot for the stars and never let self-doubt keep them from shining.”

Genesis of the Fall will mark the beginning of her writing career, and Swafford hopes it will inspire others in the community to pursue their own creative passions.

A smorgasbord of colors

Each year, as September fades into October, the northern Cumberland Plateau begins its slow, spectacular transformation to autumn. For those who want to catch the show at its peak, preparation is half the experience. The high ridges and deep gorges of this part of Tennessee — stretching across the Big South Fork National River & Recreation Area, Frozen Head State Park, the Obed Wild & Scenic River, and the vast North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area — deliver some of the most dazzling fall color in the Southeast. But timing, planning, and awareness of the terrain are crucial to making the most of the season.

The leaves begin their change earliest at higher elevations, usually in the last week of September or the first week of October. Frozen Head, with its peaks climbing to more than 3,000 ft., is often among the first places to show color. By mid-October, the palette has spilled down into the Big South Fork, where hardwood forests cling to the walls of sandstone gorges, and maples, hickories, and sourwoods set the ridgelines ablaze. The Obed, with its cliffs and hidden hollows, usually follows a similar pattern. Lower elevations in the North Cumberland WMA, which sprawls across more than 140,000 acres of rugged terrain, often hold color well into late October and even November, giving the Plateau one of the longest fall seasons in the state. Visitors planning multiple outings can chase the season as it rolls down from mountaintop to valley.

To prepare for a trip, consider the style of adventure you want. Hiking is the most intimate way to experience fall, and the Plateau’s network of trails is vast. Big South Fork alone offers hundreds of miles, from short jaunts like the Twin Arches loop to longer backcountry treks. Frozen Head’s Lookout Tower Trail is strenuous, but on a clear fall day the view from the top can stretch across a sea of crimson and gold ridges. The Obed caters not only to hikers but to rock climbers and paddlers, who find the colors reflected in the swift-moving waters below sandstone bluffs. Hunters in the North Cumberland WMA, meanwhile, share the woods with leaf-peepers, and October is a busy month with archery deer and bear seasons underway. Visitors should know where they’re going and wear bright clothing if venturing into hunting zones.

Preparation means more than marking the calendar. Autumn weather on the Plateau can be fickle. Warm, sunny days often give way to chilly nights, and an unexpected cold front can drop temperatures quickly. Dressing in layers is essential, as is carrying rain gear — cloudbursts can sweep across the Plateau with little warning. Good footwear is another necessity; trails may be littered with wet leaves that hide slick rocks or roots. If you’re venturing into more remote areas, a detailed map and a plan for limited cell service are wise precautions. Many parts of the Big South Fork and North Cumberland feel wild and isolated, and it’s best to be self-sufficient.

Travelers should also prepare for crowds. While the Plateau is never as overrun as the Great Smoky Mountains during peak foliage, weekends in mid-October can still bring heavy traffic to trailheads and overlooks. Planning a weekday trip or starting early in the morning often means a quieter experience. For photographers, early light or late evening produces the richest colors and avoids harsh midday glare. Carrying a thermos of coffee or cocoa and taking time at an overlook can turn a hike into a lingering memory rather than a hurried outing.

Ultimately, fall on the northern Cumberland Plateau is about patience and presence. Unlike a single event, the season is a slow unfolding, a cascade of colors moving down the mountainsides day by day. Preparing well—whether with maps, gear, or timing—ensures you don’t miss the best of it. But just as important is being ready to pause: to sit on a sandstone ledge in the Big South Fork, to breathe in the cool air at Frozen Head, to watch leaves swirl in the Obed, or to stand in the vast, wild expanse of the North Cumberland. Fall here is fleeting, but it rewards those who prepare with a spectacle that feels both timeless and brand new.

Sacred Ground: A.J. Robbins Cemetery

Located off Gib Griffith Road in the Slick Rock area of Brimstone, the A.J. Robbins Cemetery is a small, peaceful burial ground on a knoll overlooking Brimstone Creek and the old railroad that once ran through this valley.

Only 15 people are buried at the A.J. Robbins Cemetery, but it remains active. Several people have been buried there in the 2000s — including one just two years ago.

The Robbins family

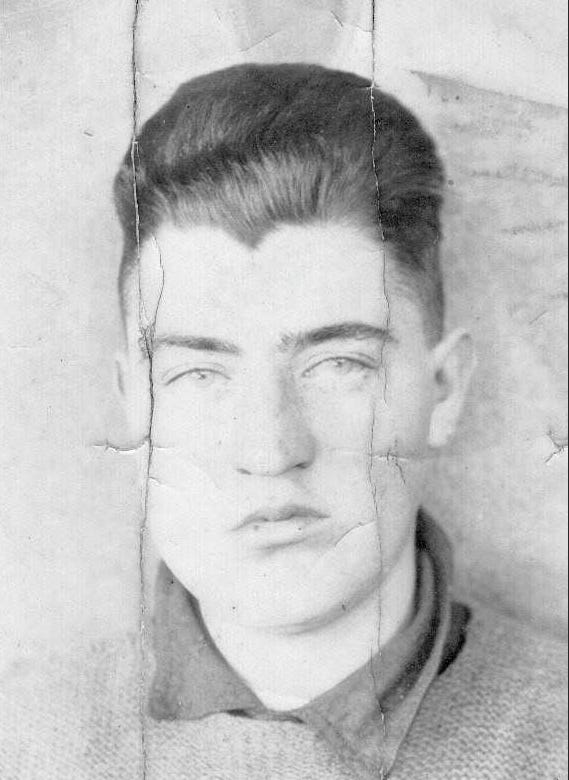

A.J. Robbins was Andrew Johnson Robbins, named for the U.S. senator and future president who had left a favorable impression on Scott County.

Johnson visited Scott County, along with Congressman Horace Maynard, in June 1861 to urge people here to vote against disunion. Four days later, Scott Countians voted against secession by the largest margin of any county in Tennessee: 521-19. Johnson then urged President Abraham Lincoln to send federal troops into East Tennessee to liberate the pro-Union region from the grips of the Confederacy.

The result of Johnson’s urging to Lincoln was the organization of Camp Dick Robinson in eastern Kentucky, near Danville. The first federal army base south of the Ohio River, it was built for the purpose of raising a 10,000 man army and training them before launching an invasion of Scott County and East Tennessee. Many men from Scott County and the rest of the eastern portion of the state went to Camp Dick Robinson to enlist and join the fight.

Although he didn’t enlist at Camp Dick Robinson, one of those who enlisted was A.J. Robbins’ father, William Robbins (1832-1863). He lived in the Slick Rock area of Brimstone and was instrumental in the formation of the Scott County Home Guard in December 1861. He and 70 other men met at the Scott County Courthouse in Huntsville and pledged an oath of loyalty to the Union and each other, and Robbins was the first man to affix his signature to the paper.

In response, a regiment of Confederate soldiers under the command of Col. John C. Vaughn — a former sheriff in Monroe County, Tenn. — arrived at Brimstone Creek on April 1, 1862 searching for Robbins. What resulted was the Battle of Brimstone, a skirmish at Robbins’ home that left the Rebels defeated and a few men dead on either side.

Following the battle, William Robbins formally enlisted in the Union army and was commissioned a captain in the 7th Tennessee Infantry, which was being organized in Huntsville by Col. William Clift of Chattanooga. The 7th Tennessee was routed by Confederates at the Battle of Huntsville in August 1862, and after spending a few months rooting out guerrillas who were raiding and looting in the North Cumberland region, the soldiers were ultimately reassigned to outfits in Kentucky. It was in Lexington, Ky. that William Robbins fell ill with typhoid fever and died on April 16, 1863, at the age of 30.

A.J. Robbins never knew his father; he was only six months old when William Robbins died. His mother, Lucinda Lewallen — daughter of Joel Lewallen (1803-1892) and Rachel Sue Taylor (1798-1892) — lived with and had several children with John Hughett (1824-1908), a prominent Brimstone man who served 44 years as a justice of the peace (now known as county commissioner). John’s sons, Jasper Hughett and Frank Hughett, had married the daughters of William and Lucinda Robbins; Jasper married Vicie and Frank married Amanda. Like their father, the Hughett brothers were well-known in south Scott County. Jasper was a businessman and merchant in Robbins, and Frank was elected sheriff of Scott County.

It is written that Robbins — which was first a railroad depot, and then the town that sprang up around the depot — took its name from A.J.C. Robbins, a man who may have worked on the railroad. We don’t know if that’s the same A.J. Robbins as Andrew Johnson Robbins of Brimstone Creek, but it seems likely that it was from this family that the town of Robbins took its name.

The Robbins family had come to Scott County with A.J. Robbins’ grandfather, Michael Robbins, who married Mary Lewallen, daughter of Anderson Grant Lewallen and Lydia Rice of Glenmary. Michael was born in Virginia in 1781. His father was believed to be John Robbins (1741-1834). There’s some question about the lineage, with some family trees indicating that John Robbins was born in Wales and others indicating that the family had actually been in the American colonies — settling in New Jersey — for a couple of generations by the time John Robbins was born. Either way, John Robbins moved south to Virginia, and from there his son, Michael, came on to Tennessee.

Once they arrived at Brimstone Creek, the Robbins family flourished. Vicie and Manda — the sisters who married the Hughett brothers — both died young. (Vicie is buried at Hughett Cemetery near Slick Rock; we don’t know where Manda was buried.) Dr. Horace Maynard Robbins (who wasn’t William’s son, but was one of Lucinda’s sons with John Hughett) served as a superintendent of schools but eventually left for Oregon. (Incidentally, Congressman Horace Maynard had also visited Scott County with Sen. Andrew Johnson in June 1861, and in the process lended his namesake to another of the Robbins boys.)

But it was with A.J. Robbins that the family legacy really cemented itself in southern Scott County. A.J. married Julia Ann Hughett (1861-1937) in 1881. She was the daughter of William Alexander Hughett Jr. (1836-1913) — a brother to John Hughett — and Sarah Marie Delk (1835-1918). They had 13 children. (Capt. William Robbins had a brother, John Robbins, whose son, Melton James “Mitt” Robbins, was elected Scott County Judge and later served in the state legislature. Mitt and A.J. were first cousins.)

The cemetery begins

The A.J. Robbins Cemetery off Gib Griffith Road is believed to have started with the burial of Melton Robbins in 1891. He died in infancy, and was the eighth of A.J. and Julia Ann’s 13 children.

There wasn’t another burial on the small knoll until A.J. died in January 1923, at age 60. His wife, Julia Ann, was also buried there in 1937.

A couple of other burials took place at the cemetery between the deaths of A.J. and his wife: Opal Robbins, a two-year-old child, was buried there in 1927, and 34-year-old Joseph L. Robbins was buried there in 1933. Joseph was A.J. and Julia Ann’s son, and Opal was his daughter. Joseph, who married Arphia Long and had four children, was killed by a gunshot wound to the stomach.

Other children of Joseph and Arphia included Theodore J. Robbins (1920-1969), Ralph Lee Robbins (1923-2013), and Walter Riley Robbins (1927-1988).

Rufus Monroe Robbins was buried at the cemetery when he died in July 1947 at age 66 of a heart attack. He was also the son of A.J. and Julia Ann., who had married Essie Lawrence Jones (1894-1982). She would later be buried at the cemetery, as well. They had a son, Harold Virgil Robbins (1912-1969) who is also buried at the cemetery, as is his wife, Vera Bell Barnett (1921-2008), and an infant son, Richard Gaylon Robbins.

Horace Maynard Robbins (1901-1955), son of A.J. and Julia Ann, was buried at the cemetery in 1955. He had a son, Vernon Ray Robbins, who died in 1956 at age 10 and was also buried at the cemetery.

The cemetery today

Glenna Mae Robbins West was buried at A.J. Robbins Cemetery in 2006 when she died at age 62. She was the daughter of Silas Kermit Robbins, and the granddaughter of Rufus Monroe Robbins. She first married Claude Henry (1937-1978), who is buried at Slick Rock Cemetery. Following his death, she married Billy West. She had a total of 10 children. At the time of her death she had 35 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. She had a brother, James Kermit Robbins, buried at the cemetery in 2015.

The most recent burial at A.J. Robbins Cemetery was Glenna Mae’s son, Tracy Aaron Henry, in November 2023. He was 49 when he died, and was survived by five children and six grandchildren. He was a second-great-grandson of A.J. and Julia Ann Robbins.

Tracy A. Henry, 1974-2023

Andrew Johnson Robbins, 1862-1923

Essie Jones Robbins, 1894-1982

Harold V. Robbins, 1912-1969

Horace M. Robbins, 1901-1955

James K. Robbins, 1945-2015

Joseph L. Robbins, 1899-1933

Julia Hughett Robbins, 1861-1937

Melton Robbins, 1891-1801

Opal Robbins, 1925-1927

Richard G. Robbins, N/A-N/A

Rufus M. Robbins, 1891-1947

Vera Barnett Robbins, 1921-2008

Vernon R. Robbins, 1946-1956

Glenna Robbins West, 1944-2006

See past “Sacred Ground” cemetery profiles on the Encyclopedia of Scott County.