Scott County, Oneida and Winfield all rejected the first landfill, but then a judge ordered it anyway

A look back at how Roberta Sanitary Landfill — now Volunteer Regional Landfill — came to be

“Under any kind of review standard, (Johnny King) is entitled to the local approval he seeks. A denial would be based simply on arbitrariness.”

Those were the words of 8th Judicial District Chancery Court Judge William Inman in November 1992, 10 days after he heard a lawsuit that King had filed against Scott County and the Town of Winfield. King’s lawsuit came after the county and the town denied approval of what he called the Roberta Sanitary Landfill in the Bear Creek area north of Oneida.

King built his landfill, which today is owned by Waste Connections and is known as Volunteer Regional Landfill, and the 1992 court ruling was largely forgotten until a Chattanooga-area developer moved to purchase a chunk of the original King lands for a second landfill.

Knox Horner’s proposal to build a second landfill on approximately 700 acres of property adjacent to the 800-acre Volunteer Regional Landfill — property that was involved in the 1992 court decision — has brought that decades-old ruling back into the public eye. Scott County Attorney John Beaty told County Commission last week that any attempt on their part to reject Horner’s landfill proposal would likely constitute a violation of the 1992 court order.

With that in mind, we traveled back in time to the late 1980s and the early 1990s, delving into Independent Heraldarchives to determine what led to the judge’s ruling.

Inman’s ruling in November 1982 capped a three-year debate over the future of the approximately 2,000 acres of land that King owned in the Bear Creek area — land he had first sought permission to build a landfill on six years earlier. In 1989, after the Tennessee General Assembly passed the so-called Jackson Rule that gives county and municipal governments more control over privately-owned landfills, both Scott County Commission and the Town of Winfield attempted to stop King’s landfill plan. King filed a $10 million lawsuit naming both governments as defendants.

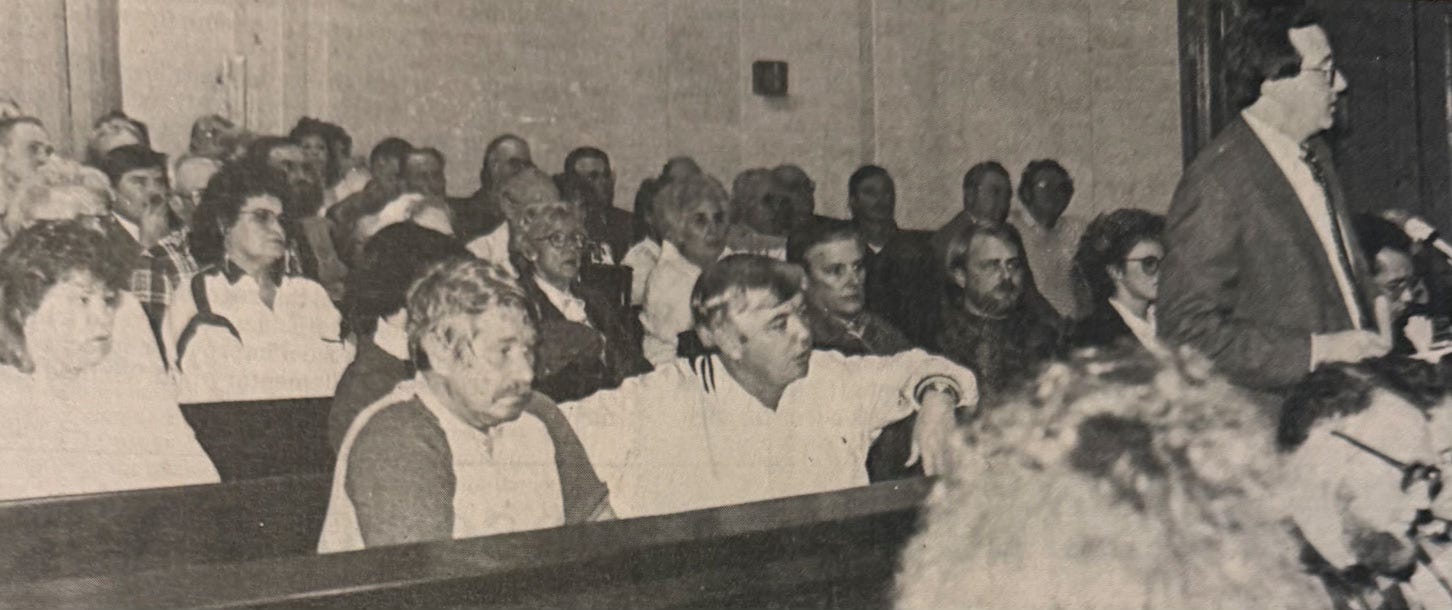

In the fall of 1992, County Commission attempted to reach a settlement with King, and appeared to be close to doing so. In fact, County Commission and the Winfield Board of Mayor and Aldermen met in a rare joint session at the old county courthouse in Huntsville in October 1992, prepared to accept that settlement. But as Scott Countians crowded into the courtroom, ready to protest any agreement that might be forthcoming, they were informed that there was no agreement, after all. The matter was headed to trial.

Ten days after hearing testimony from both sides, Inman ruled that Scott County and Winfield had no legal leg to stand on in their attempt to deny King’s request for local approval of his landfill. He based his decision on Tennessee law that states, “…the legislature places in the hands of the commissioner of the Department, rather than with local governments, the responsibility to approve plans” for landfill construction.

Scott County was represented at the time by County Attorney William Cooper III, while Winfield was represented by James L. (Jamie) Cotton Jr.

Inman ruled at the onset of the hearing that Cooper and Cotton could not offer testimony or cross-examine King’s witnesses. That led Cooper to say that Inman had misinterpreted the law and that the county would file an appeal.

Ultimately, that appeal was unsuccessful.

According to an Independent Herald article written at the time, King’s landfill plans were in the process of being approved at the state level when the Tennessee General Assembly approved the Jackson Law in 1989 and Scott County Commission adopted that law, requiring local approval for the landfill. When that happened, the state placed its process on hold until King could obtain local approval. However, both the county and the Town of Winfield rejected his plans after rooms full of people turned out to voice objections at public hearings.

So why did Inman say that testimony in opposition to the landfill — including letters written by neighboring landowners — could not be introduced at the hearing? He was ruling in favor of a motion that had been made by King’s attorneys. He wrote, “This motion was granted because the expression of fears, or the empirical dislike of landfills, or the purely subjective opinions of area residents cannot be considered.” Regarding the public hearings, which had brought standing-room-only crowds out on a number of occasions with almost no one supporting the landfill, Inman wrote that “the entire process became emotionally politicized.”

Like Cooper, Cotton disagreed with the judge’s decision — though he said he was not surprised by it — and pledged to appeal.

Inman was overseeing the lawsuit after 8th Judicial District Chancellor Billy Joe White recused himself.

Prior to the creation of what King called the Roberta Sanitary Landfill, Scott County had operated its own landfill in the Sulphur Creek area of Helenwood. That landfill was at the end of its life cycle, however, and then-Scott County Executive Clarence “Denny” Lowe said it would cost the county millions of dollars to stay in the solid waste business, in order to comply with a new solid waste law the state had passed in 1991. That’s because the county was going to have to build a new landfill to dispose of its trash. In fact, it had been estimated that Scott County residents could see their property tax double by the 1994-1995 fiscal year if the county had attempted to stay in the landfill business.

On the other hand, Lowe said at the time, Scott County could broaden its tax base and gain money for education and lowering the tax rate by permitting the landfill. He acknowledged that commissioners probably couldn’t vote for the landfill due to the political pressure being generated by those opposed to it, but he told the Independent Herald: “I can tell you this … if it comes to a tie vote I know how the county executive will vote (to break the tie).”

In an editorial that fall, Independent Herald editor Paul Roy wrote: “Politically, the 14 members of County Commission are between a rock and a hard place on this issue — if they go ahead and fight Roberta Sanitary Landfill in Chancery Court and lose, then they’re likely to be booted out of office because of what that would do to the tax rate. If they win the lawsuit, they still face a similar, never-ending payoff on maintaining a county owned and operated landfill, with the same end result.”

Weeks later, it was revealed that a new county-owned landfill would cost Scott County more than $13 million to build, and $1.8 million per year to maintain. Options discussed by County Commission for funding that cost included a property tax increase, a wheel tax, and a tipping fee, as well as mandatory trash pickup in all of Scott County.

Ultimately, however, the county opted to build a trash transfer station at the Sulphur Creek Road site of the old landfill, and establish convenience centers at six communities throughout the county, for the purpose of transporting trash out of the county. It was estimated that the initial cost would be $1 million, with a cost of about $700,000 each year thereafter.

It was in October 1989 that the proposed landfill exploded into a front-burner issue. On Oct. 16, 1989, a standing-room-only crowd showed up at the old county courthouse in Huntsville to oppose the landfill, after word leaked out that an attorney for landowner Johnny King — who was represented by Sherman Fetterman — would be asking County Commission to publish a notice of proposed landfill.

That publication, which Scott County was required by state law to do, set off the landfill tug-of-war that didn’t end until the Chancery Court’s ruling nearly three years later.

Ironically, one of the big stories of 1989, prior to October, had been a proposal for a 500-acre lake at Bear Creek to provide drinking water for the Town of Oneida. It was a project that was seen as a long shot, due to the fact that Bear Creek was heavily polluted due to past coal mining along the stream, and — doubly ironic — the fact that there were several illegal dump sites close by.

Ultimately, of course, the lake didn’t happen and the landfill did. But none of that was the desire of local officials. Oneida Mayor Denzil Pennington made it clear that he wanted the lake … and Scott County Executive Dwight Murphy made it clear that he didn’t want the landfill.

As for King, he attempted to sweeten the pot by offering $300,000 per year to the Oneida Special School District if the Town of Oneida would apply for a landfill permit on his behalf. The Oneida schools were struggling at the time; the dilapidation of the existing school buildings had been a major topic of conversation, and money was being raised to build new schools.

Representing King, Fetterman told the Oneida Board of Mayor and Aldermen that he wanted a decision then and there — that very night. Otherwise, he said, he would approach the Town of Winfield with a similar offer.

Oneida didn’t take the bait; the board voted to hold two public hearings to let the public speak on the issue.

As the debate sharpened, tensions flared. Speaking at one of the public hearings in Oneida, one resident called Fetterman the “F. Lee Bailey of Scott County,” a reference to the infamous criminal defense attorney who took the cases of several high-profile murderers, including the Boston Strangler.

For his part, Fetterman complained that fellow attorney Steve Marcum — the longtime attorney of the Industrial Development Board of Scott County — had “divided loyalties” because he was representing a citizens group that had formed to protest the landfill. King was hoping to obtain financing from the IDB to build the landfill. He originally had requested $3 million of bonds, then later increased the request to $5 million.

Marcum fired back with a letter in the Independent Herald that Fetterman’s insinuations “are without any factual basis and were apparently raised by him in an effort to hide the fact that neither he nor his client fully complied with the conditions of their May, 1989, preliminary agreement with the ID Board.”

One of the many public hearings saw more than 200 people turn out at the county courthouse and speak for several hours against the landfill project.

Weeks later, in December 1989, County Commission officially rejected the landfill request.

Meanwhile, after both Oneida and Winfield rejected a pledge of funding if they applied for a landfill permit, an unlikely candidate stepped to the plate: The city of Caryville. A quirk in state law allowed the Campbell County town to apply for a permit in another county. In exchange, Roberta Sanitary Landfill pledged $109,000 annually to Caryville, along with transporting all of the city’s solid wastes to the new landfill at no charge.

County Commission, of course, let Caryville know that it was opposed to the request, and Murphy traveled to Caryville to express Scott County’s opposition. Scott County’s stance was clear: it was committed to doing whatever was necessary to block the landfill — including legal action, if necessary.

Caryville pledged to move forward with the plan despite the opposition from their neighbors in Scott County. That led to a standing-room-only crowd of Scott Countians driving to Caryville for a public hearing that was required by law, where residents let their feelings be known. Nevertheless, the Caryville board voted to accept a quit claim deed for a 130-acre tract at Bear Creek on which the landfill was to be built — after which the board promptly adjourned and exited the meeting room without walking through the crowd.

Just weeks later, however, the Caryville board did a surprise about-face when it voted narrowly to reject the landfill.

King followed the Caryville decision by filing a lawsuit in Scott County Chancery Court, naming both Scott County and the Town of Winfield as defendants. Dick Sexton, Scott County’s future road superintendent, was Winfield’s mayor at the time.

The lawsuit accused local officials of conspiring against the landfill, and said that Murphy had “actively waged a campaign designed to prevent the approval” of the landfill.

In May 1990, King withdrew his lawsuit, and renewed his petition to County Commission for a landfill permit. Again a standing-room-only crowd of hundreds turned out to protest the landfill, and again County Commission voted against it — this time by a 13-1 vote.

Again a lawsuit was filed, this time requesting $10 million in damages, which led to the 1992 court decision paving the way for the landfill to be built despite Scott County’s objections.