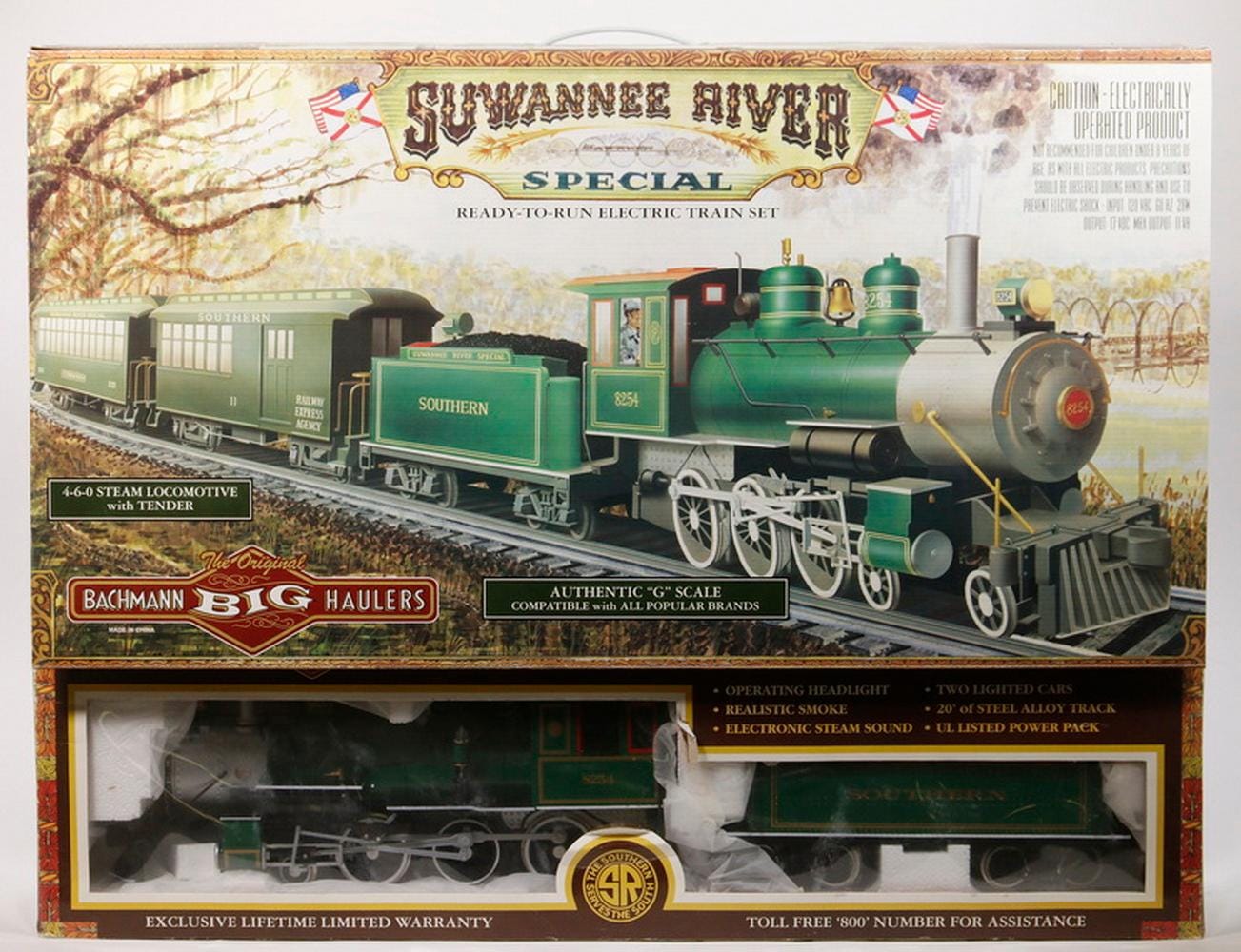

The 1931 train crash near New River that claimed five lives

Suwanee River Special derailed after passing Helenwood at a high rate of speed

You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

The Helenwood crash of the Suwanee River Special

The Southern Railroad had experienced a major tragedy in Scott County in 1929, when the Ponce de Leon passenger train derailed near Glenmary, killing five people and injuring dozens more.

Just two years later — on Jan. 24, 1931 — disaster struck again on the rails through Scott County. This time, the Suwanee River Special derailed near New River, moments after blowing by the Helenwood station, killing five people and injuring 10 more.

It marked 10 railroad fatalities in Scott County in two major accidents less than 24 months apart.

What happened?

Writing for the Independent Herald years later, historian Lillard Terry painted a grim picture of destruction, saying that the train was almost two hours behind schedule and doing a hundred miles an hour to make up time as she screamed down the tracks.

“They had been making up time all the way from Danville and with full steam and running all out the Special screamed through Oneida like a cannonball,” Terry wrote. “Experienced railroaders who were there that day estimated she was doing a hundred miles per hour.

“Oneida’s station master hurried to the telephone and whirled the crank furiously to inform the next station, as was his duty to do, that the train was passing Oneida. As the Helenwood agent, Crit Phillips, answered the phone he heard the shrill, high-pitched wail of the Special’s steam whistle.

“‘She’s already here,’ he answered, and ran outside to watch in awe as the great streamliner sailed past him and diminished in the distance.

“Phillips shook his head in disbelief, saying, ‘He’ll never make it to New River.’

“Phillips was right. Only seconds later he heard the horrible, shattering clamor and felt the shock of a crash that seemed to shake the entire countryside.

“Within moments after the crash a number of nearby residents of the Helenwood, Oneida and New River areas were on the scene. Many of them were sickened by what they saw. Some passengers were badly smashed up and in those cars that had been sliced by the jagged rocks, human bodies were ripped into pieces to an extent that it was impossible to determine identification of the passengers.

“One Scott County man remembered he had been going in the door of a store and he had heard the crash, although it was several miles away. His father was a Southern Railroad employee and the two of them grabbed what transportation they could and hurried down there.

“Bart Hagemeyer, one of the owners of the O&W Railroad, was in Oneida and he and Cicero Lewallen and some other friends then proceeded down there to offer their help if needed.

“Immediately following the crash the surviving crew members and some of the surviving passengers, though still in a confused state, were rushing about trying to help where they could.

“Many of the passengers in the crash were beyond help. The train had jumped the tracks on an outside curve in the area near tunnel 13, north of New River. Some of the cars, rolling at this high speed, were thrown into the embankment from which big, jagged rocks protruded. These big rocks sliced through those cars like (in the words of an observer) a jagged knife through a bowl of butter.”

Facts of the crash

The official report from the Interstate Commerce Commission painted a less dramatic picture, though it concurred that excessive speed had been the cause of the crash.

The train — officially called Passenger Train No. 5 — had departed Chicago, Ill. and picked up more passengers during a stop in Cincinnati, Oh. before a stop in Somerset, Ky. to change crews. It was scheduled to make another stop in Oakdale, Tenn.

The train — consisting of a combination baggage and coach, one coach, one dining car, and six Pullman sleeping cars, pulled by Engine 6477 — was four minutes behind schedule when it passed the Pine Knot station at 12:32 p.m. on Jan. 24, 1931, according to the ICC’s report. The train passed the Helenwood station between 12:40 p.m. and 12:45 p.m., at an estimated speed — according to witnesses — of 50 mph to 55 mph.

Just under a mile south of the Helenwood station, near Tunnel No. 13 north of New River, the train derailed on a slight reverse “S” curve. All cars derailed, though some remained on the railbed.

The engine and tender derailed and came to rest against an embankment. The front end of the engine stopped 279 feet south of the initial point of derailment. The first and second cars continued beyond the engine for a distance of 956 feet, with the first car stopping upright, while the second car overturned and skidded the entire distance on its side.

The third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh cars were partially overturned, while the two rear cars remained upright. The third car stopped 350 feet south of the engine and the rear car stopped at the initial point of derailment.

The engine and first seven cars were badly damaged, while the eighth and ninth cars were slightly damaged.

Eyewitness statements

The train’s conductor, identified by the ICC only as “Huskins,” told investigators that the train’s brakes had been tested before leaving Somerset and appeared to be fine. He estimated the train’s speed at 50 mph to 55 mph at the time of the crash, and said it was the normal operating speed. He was riding in the first car behind the engine and said he first noticed trouble when he felt an application of the brakes two to three seconds before the derailment occurred. He said the derailment occurred at 12:58 p.m.

The baggageman, identified as “Brown,” was also riding in the first car and said he felt no application of the brakes prior to the derailment. He also estimated the speed at 50 mph to 55 mph. He overheard the conductor say what time the accident occurred, but couldn’t remember if Huskins said 12:48 p.m. or 12:58 p.m. He left the train to flag oncoming rail traffic ahead of the accident site.

The flagman, identified as “Sharp,” was in the rear car. He said the train seemed to “slacken speed and then began to surge” just before the derailment. Like the others, he estimated the speed at 50 mph to 55 mph. He left the train to return to the Helenwood station and report the accident.

The train porter, identified as “Wellington,” was in the first car of the train and said he heard a slight noise and looked up to see that the engine had separated from the rest of the train. Like the others, he estimated the speed at 50 mph to 55 mph.

The section foreman, “Judd,” was near the Helenwood station when the train passed. He, too, said it was traveling an ordinary rate of speed — about 55 mph. One or two minutes later he heard a noise to the south, “which resembled escaping steam and the drivers of an engine slipping on the rails.” He saw a flagman approaching from that direction soon thereafter and hurried down the track to assist.

A railroad agent, “Whisenhunt,” had just returned from lunch at the Helenwood station when he heard the train’s whistle, which he said occurred at 12:40 p.m. or 12:45 p.m. He was standing on the station platform when the train passed, and said it was traveling at an ordinary speed. The engineer was sitting in the cab with his eyes open and appeared to be okay, Whisenhunt said. He said he heard the hiss of escaping steam a short time later, and reported the accident to the dispatcher when the flagman reached the station.

The conclusion

Throughout the day on Jan. 24, various railroad authorities arrived at the Helenwood station and conducted examinations of the train and the track. All of the men concluded that the rails were safe for trains to operate at the maximum allowed speed. One of them, a supervisor named “Barron,” believed that a radius bar broke, causing the train to not track properly, and that the engineer applied the brakes when he noticed that, causing a strain that broke the frame.

A maintenance supervisor, “Hayes,” also believed a break had occurred in the radius bar that contributed to the accident. An assistant superintendent, “Higgins,” didn’t form an opinion on the radius bar, but concluded that the air brakes had been heavily applied, lifting the back drivers off the track.

On Feb. 25, 1931, ICC Director W.P. Borland released a report stating that the accident “probably was caused by excessive speed.”

He wrote: “On account of uncertainty as to the exact time of the accident, it is impossible to say definitely at what average speed the train had been operated between the last open office and the point of accident, a distance of 19.7 miles. The condition of the equipment after the accident, however, coupled with the manner in which it came to rest, the nature of the damage sustained, and the absence of flange marks at the point where the derailment is believed to have occurred, indicate quite clearly that the estimates as to speed made by the surviving members of the crew must be considered as minimum estimates. In all probability the speed was in excess of 60 miles per hour, and it would appear that this high rate of speed resulted in the overturning of the engine and that the principal damage to the trailer truck was caused by the first two cars as they passed the derailed engine, these cars also causing other damage to the left side of the engine, such as the guide, guide-yoke extension, and back end of the left cylinder.”

Borland cited statements made by railroad employees who had inspected the train before it left Somerset, Ky. — who said it was in normal operating condition — as proof that the trailer radius bar did not break and contribute to the derailment. He said that inspectors’ belief that the radius bar had broken due to a stuck wedge was disproven by “subsequent inspection (which) failed to develop anything wrong with the wedges.” And, “while it is possible a broken radius bar contributed to the accident, it is believed that high speed was the principal factor,” he wrote.

The dead

The train’s engineman was killed in the accident, as was the fireman. Both were traveling in the engine. Three passengers riding in the overturned car were also killed.

The engineer was Harry Lindle. The fireman was Charles Sexton, of Sunbright.

The accident marked the third deadly train derailment on the Southern Railroad in Scott County in a six-year period. In addition to the crash of the Ponce de Leon, a passenger train had derailed at low speeds near the Helenwood station in 1925, killing two people, the engineman and fireman.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The Weekender Thursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)