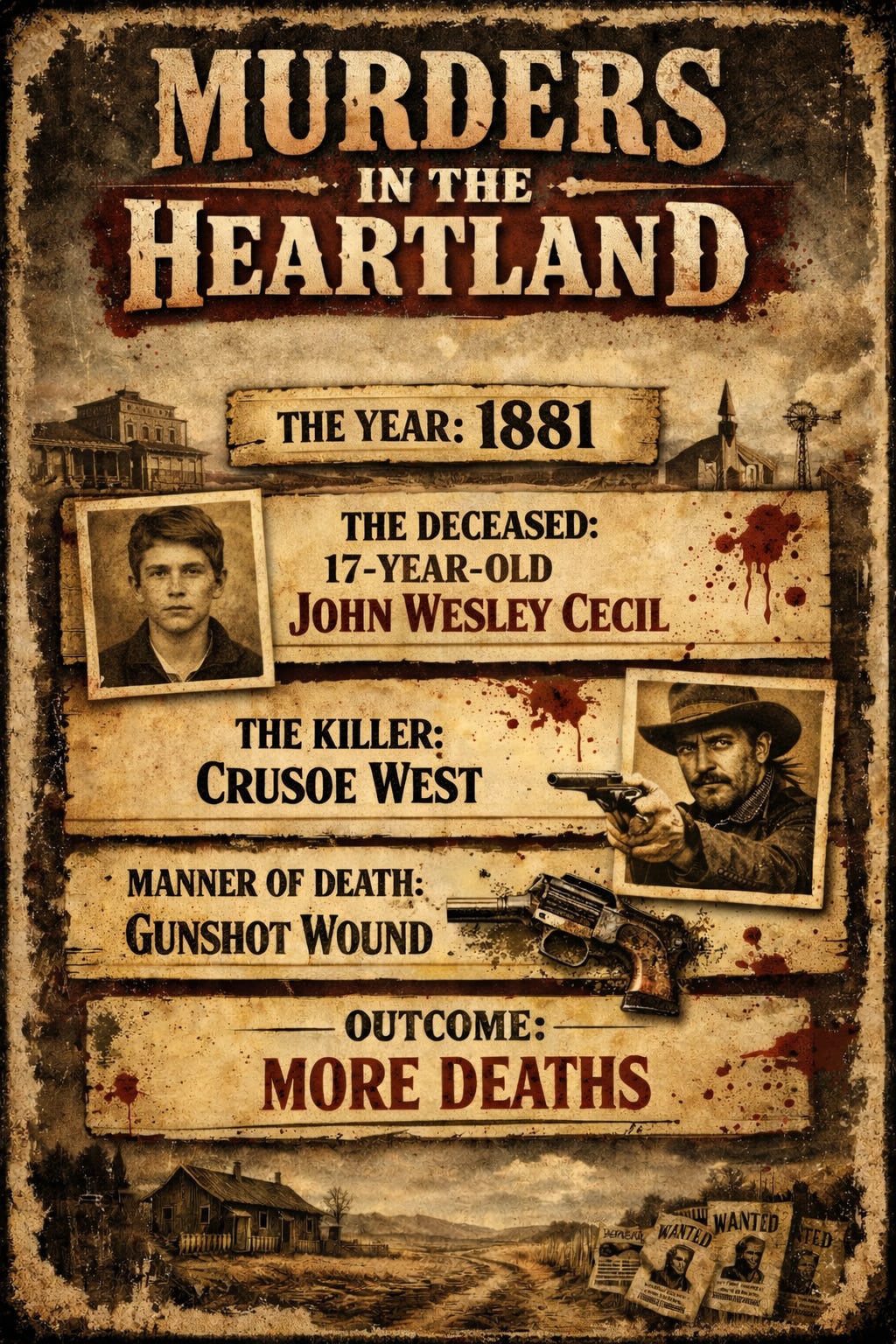

The Cecil-West-Smith feud of the 1880s

Four men died, including three brothers, in a feud that began in a Helenwood saloon on Christmas Eve in 1881

You’re reading Friday Features, a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. If you’d like to adjust your subscription to include (or exclude) any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t subscribed, please consider doing so!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

Murders in the Heartland: The Cecil-West-Smith feud of the 1880s

Christmas Eve, 1881

If you’re spending Christmas Eve in a railroad-town saloon, you probably aren’t there for peace and goodwill. You’re probably there because it’s cold outside and warm inside, because the whiskey is cheap and the company is familiar, and because going home to whatever waits there seems less appealing than one more drink in a room full of men you’ve known your entire life.

The saloon in Helenwood wasn’t much to look at. There was a crooked piano that couldn’t hold a tune. Sawdust on the floor. The kind of place where the walls had soaked up so much tobacco smoke and spilled liquor that they’d turned the color of old leather. On Christmas Eve 1881, John Wesley Cecil sat at a table with his uncle, Robinson Crusoe West. Nobody in the place was thinking about baby Jesus or silent nights.

John was seventeen. Crusoe was twenty-four. One newspaper would later call them “companions in mischief and deviltry,” which is just a fancy way of saying everybody knew not to cross them. The newspaper went so far as to say they were “considered by the community as bad and dangerous men.”

Crusoe had already killed a man and done time for it in the state pen. He was lean and quick, with the kind of reputation that made other men give him space. They called him “Crusoe” after the Daniel Defoe character, but he wasn’t the type to get shipwrecked and wait for rescue. He was the type who’d burn the island down and build a raft from the ashes.

Earlier that day, John and Crusoe had ridden out of town and fired their pistols into the hills. Just fooling around, the way young men with idle time on their hands might do then or now. But there had been drinking, too, and by the time they got back to the saloon, something had changed. Maybe it was the whiskey. Maybe it was just the way these things go sometimes – two young men with guns and too much pride and not enough sense to back down.

Anyway, one thing led to another and Crusoe said: “Let’s shoot it out.”

John didn’t hesitate: “Shoot!”

The guns came up and the shooting started. Crusoe took a bullet in the cheek that lodged against his ear. John caught one in the chest but stayed on his feet. Then the whole room went to hell.

Other men jumped in – Jerry West, Charles West, William West, and George Thompson were names that appeared in the newspapers as being involved. Tables went over. Fists and knives and more gunfire. Nobody could say later exactly who did what or why. But when it was over, John Wesley Cecil was on the floor, bleeding out.

By nine o’clock the next morning, he was dead. Christmas had dawned with tragedy in the Cecil household.

They buried John on the family land at Cherry Fork. He was the first grave in the new family cemetery. He would not be the last. And you can’t help but imagine that his father, William Riley Cecil, stood there and watched them put his boy in the ground, making himself a promise to avenge his son’s death.

***

Crusoe West didn’t run. He probably should have, but he was too shot up to run. He made it home and crawled into bed, and that’s where the Cecils found him.

William Sr. and his sons rode in with a warrant they had sworn out. It was legal and proper. But when old man Cecil told Crusoe that he was under arrest, Crusoe just shook his head.

“I’ll go with the sheriff,” he said, “but I’ll never go with a Cecil.”

Somebody made a move. Somebody raised a gun. Who? Who knows. But the shooting started again.

When it was over, Crusoe West had more than a dozen bullet holes in him. Three of those came after he was already dead, the newspapers said.

But the Cecils paid for it, too. Reason Burl Cecil – John’s older brother – took a knife in the fight. He held on for a while, but died on January 10, 1882.

Huntsville attorney Don Stansberry provides a paper that was given to him by John Toomey Baker years ago, though he said he has no way of knowing whether any of the details in it are true. On the paper, there’s a notation that it was originally provided by James E. Phillips in the 1950s. It is a list of men killed in or near Helenwood through the years, and it provides details that didn’t appear in the newspapers.

Specifically, it states that when the Cecils went to Crusoe’s home, the gravely wounded West told his wife to let the men in and leave the room. Telling Burl Cecil to bend over because he wanted to tell him something before dying, Crusoe stuck a knife in his back, and then was killed by the rest of the men.

While there’s no way to vouch for the accuracy of the paper, it explains why a mortally wounded West would have been able to knife another one of the Cecils from his bed.

Now there were two Cecils dead, along with one West. And still the killing wasn’t finished.

***

May 27, 1883. A Sunday evening in Helenwood.

William “Riley” Cecil Jr. was twenty-seven. He had a wife named Lucinda and three boys. He’d been trying to build a normal life after helping bury two brothers. Trying to keep his head down and his nose clean, you might say.

But old grudges don’t care about someone else’s good intentions.

That evening, Riley and his father ran into the Smith boys – John, Jerry, and Gilbert, if news reports are accurate. They were kin through the Wests. Cousins. And the guns fired one more time.

Nobody agrees on how it started. Some said the Smiths wanted payback for their father – that’s what the Knoxville newspapers reported, though if the Cecils actually killed him it’s impossible to prove by the historical record. The newspapers made up half a dozen different versions, each more dramatic than the last.

What actually happened was simpler … and, at the same time, maybe worse: guns came out, shots were fired, and Riley Cecil dropped with a bullet in his head before he even got his weapon up. His father fired ten times before he went down, wounded but alive.

The press went crazy. Newspapers throughout the South wrote about the big feud up in Helenwood. The Chattanooga Times said both Riley and his father were dead. The Knoxville Tribune claimed five people died. Names got jumbled. Some papers said one of the Smiths got hunted down and killed by a posse afterward.

None of it, apparently, was true, except that Riley Cecil – a third brother – was dead.

The Plateau Gazette, down in Morgan County, got it mostly right: four men dead in total. John Wesley Cecil, Reason Burl Cecil, Crusoe West, and Riley Cecil. The Smiths – Gilbert, John, and Jerry – turned themselves in. Nobody else died.

Riley, meanwhile, joined his brothers in the cemetery at Cherry Fork. Now three sons buried in less than two years, and the grief felt by William R. Cecil Sr. and his wife, Nancy, must have been overwhelming.

***

Feuds make good gossip but bad history. The truth gets all tangled up in that gossip and newspaper headlines and what people think they remember. And by the time it’s all sorted out, nobody knows for sure who started what or why.

By late June 1883, the newspapers that had gotten all the details of the last gun battle so mixed up had more or less sorted out. They stopped reporting Riley’s father as “John” and reported it as “William,” and stopped reporting that he’d been killed and reported he’d been wounded instead. What appears to be most likely is that the original newspaper reports confused the Christmas Eve 1881 bar shooting with the events that followed.

The Smith boys had surrendered by law enforcement by that time, though the pursuit of justice was apparently not a story worth following and the newspapers lost interest.

Beyond that, here’s what we do know:

The Smith boys weren’t strangers to the Cecils. Their mother, Sarah Elizabeth West, was a sister to both Crusoe West and Nancy West Cecil, mother of the Cecil boys. They were all cousins. Family killing family over something that started with a drunken dare on Christmas Eve.

The Smiths went by different names in different records: Smith, then Sexton. Gilbert Sexton ended up fighting in the Spanish-American War, came home, and served three terms as sheriff of Scott County.

John Smith moved to Anderson County and worked in the coal mines until he died of cancer in 1929.

Jerry Smith settled down in Helenwood with his wife, Martha, and lived out his days.

The women did what women always do – they survived. Lucinda remarried and had more children. Crusoe’s widow, Arlena, lived another fifty years but never married again. Their daughter, Sylvania, lived quietly and was buried in Duncan Cemetery.

And the Cecils carried on. George Washington Cecil – a brother to the three dead boys – became a Baptist preacher. His grandson pastored Helenwood Baptist Church for thirty-seven years. His great-grandson pastored it for another thirty-three.

The family that lost three sons to gun violence ended up producing generations of preachers. Beaty Cecil – one of Riley’s sons, who was just a boy when his father was gunned down – later served as Sunday school superintendent for many years at the old Cherry Fork Baptist Church.

***

Helenwood is quiet now. The saloons are long gone, and the town’s 1880s reputation as a rough and rowdy whistle stop on the Southern Railroad has long since disappeared. The feud that killed four men and split a family right down the middle has faded into something that has mostly been forgotten.

Time did what bullets couldn’t. It ended the war.

At Cherry Fork, the headstones at Cecil Cemetery stand testament to three brothers whose lives were snuffed out too soon. John Wesley, seventeen when he took that dare in the saloon. Reason Burl, stabbed going after his brother’s killer. Riley, shot down on a Sunday evening when he maybe thought the worst was behind him.

The piano has been silent for over a century. The guns are rusted. The people who descended from those families carry their names without the weight of what happened in 1881 and 1882.

Peace came late, but it came.

The mountains don’t forget. They never do. They just keep standing there, patient and old, watching families tear themselves apart and then, eventually, put themselves back together.

It’s been that way since men first settled these hills.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment in the revised “Murders in the Heartland” series, and was not included in the original series that published three years ago. It should be noted that there are multiple people in this story who have identical names to others from Scott County through the years. Robinson Crusoe West had a distant relative also named Crusoe West who was famous for living in a cave in the Pine Hill community, a story later related by the FNB Chronicle. Beaty Cecil, son of Riley Cecil, is not the same Beaty Cecil who served as Scott County Sheriff in the 1880s and was father of the “Fighting Cecils” of New River. That was a different branch of the Cecil family.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletter will be The Daybreaker bright and early Monday morning. If you’d like to update your subscription to add or subtract any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t yet subscribed, it’s as simple as adding your email address!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes from the Past (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)