The curious case of Scott County's Hessian surgeon and his Glenmary 'fort'

Gustavus Brandau was a physician who lived in Scott County for a time and represented Scott County when East Tennessee pushed for independent statehood. But who was he really?

You’re reading Friday Features, a weekly newsletter containing the Independent Herald’s feature stories — that is, stories that aren’t necessarily straight news but that provide an insightful look at our community and its people. If you’d like to adjust your subscription to include (or exclude) any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t subscribed, please consider doing so!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by First National Bank. Since 1904, First National Bank has been a part of Scott County. First National is local people — just like you. Visit fnboneida.com or call (423) 569-8586.

Scott County’s Civil War-era German doctor

One of the more intriguing early settlers of Scott County is a man who didn’t stick around too long, and one that very little is known about. That man was Dr. Gustavus Reynard (also spelled Reinhardt) Brandau, and perhaps the fact that we know so little about him is part of what makes him so intriguing.

But Dr. Brandau — G.R. Brandau, as he was often called — is also intriguing because of who he was. He was an early postmaster in Scott County, and his post office (which would have been at his home) was referred to as “Fort Brandau.” It likely wasn’t a fort in any military sense; the post office opened in 1857 and closed in 1860, before the Civil War began. Still, the name alone conjures up all sorts of images and possibilities.

Sadly, we don’t know much about Gustavus Brandau, including what brought him to Scott County. What little we do know is gleaned through old census records and various other government documents that are still in existence. He arrived in Scott County sometime between 1855 and 1857, and left around 1866. He apparently lived in the southern part of Scott County.

An old edition of the FNB Chronicle from the 1990s lists Scott County’s post offices and postmasters through the years (from D.R. Frazier’s 1984 book Tennessee Postoffices and Postmaster Appointments, 1789-1984. A reference is made to “Fort Brandon,” founded Sept. 2, 1857 and discontinued Oct. 22, 1860, with Gustavus A. Brandon serving as postmaster. That is almost certainly a reference to Gustavus R. Brandau, who lived in Scott County at the time.

As for the location of Fort Brandau, it seems likely to have been in the Glenmary area. Gustavus Brandau’s neighbors when the 1860 census was taken included Matthew and Rhoda Young, John and Rebecca Young, and Aaron Goad. All of them were known to be residents of southern Scott County. Matthew Young (1815-1893) was one of the most prominent residents of Glenmary. He married two of the daughters of Rev. Andrew Leutian Lewallen (first Elizabeth; then, following her death in 1845, Rhoda). He and both wives are buried at Campground Cemetery near Coal Hill.

It seems odd that a man of Gustavus Brandau’s stature — postmaster, apparently wealthy, and highly enough regarded in Scott County that he served as this community’s representative at a convention in Knoxville following the Civil War, when East Tennessee attempted to form its own state — wasn’t remembered more prominently by history. If not for that post office notation in the old FNB Chronicle, he might’ve been lost to the dustbin of time completely. But here’s what we know about this mysterious German doctor.

A stranger from Hessen

We don’t know who Gustavus Brandau’s parents were, but we know from various census records that he was born in Hessen, Germany around 1820. An old ship’s manifest shows that he sailed alone to New York on the ship Magdalena in October 1847, when he was about 27. We may never know what brought him to America. Or why he chose the Cumberland Plateau.

A couple of generations earlier, Hessians had been feared and vilified by American colonists for the role they played during the Revolutionary War. It was common for German states to maintain standing armies for hire during the 18th century. These mercenary soldiers were well-trained, very disciplined, and — whether deserved or not — gained a reputation among Americans as being ruthless on the battlefield. Because Great Britain did not maintain a very large army, it depended heavily on these German mercenaries during the American Revolution; one out of every four British ground troops during the war were Germans who were fighting not for loyalty to the British crown but for money. Many of them were from Hessen — or, Hesse-Cassel, as the state was known at the time — and therefore all German soldiers in the war became known to Americans as Hessians.

However vilified they might have been, many of the Hessians who came to America to fight fell in love with this new world, and decided to stay. In time, they were assimilated into the American culture, and their role in the war was largely forgotten.

Gustavus Brandau was not one of those Hessian soldiers, of course. He was not born until 1820. Because we don’t know who his parents were, we don’t know if his father or grandfather might have been a Hessian soldier. In any event, it was in 1857 that he arrived in New York City aboard the Magdalena.

The 1850 census found Brandau in Morgan County, living with a pair of fellow Germans — Charles and Margaret Haag, who ran a tavern. That detail alone sets a perfect scene for an old screenplay: a European doctor in a frontier saloon, somewhere between a civilization and the wilderness, plying his trade among rough-hewn settlers and hard-drinking mountaineers. Brandau’s occupation in 1850 was listed as physician. It seems that he had arrived in Wartburg — which had been founded just a few years earlier by George Friedrich Gerding, a land speculator who intended to create a series of German colonies on the Cumberland Plateau — by 1848.

By 1860, Brandau had moved to Scott County. He was 38, and he was prosperous enough to employ servants. His household included his wife, Anna, two small children (2-year-old Hemelz and 10-month-old Alexandre), a white servant named Mary Price, her 9-year-old daughter Sarrah, and a 19-year-old farmhand named John Great.

The historical records search for what became of Mary, Sarrah and John after 1860 is a dead-end. But an old marriage license in Nashville shows that Anna Brandau was Anna Waggoner, daughter of William Henry Waggoner and Elizabeth Armentrout, and that she and Gustavus were married in Nashville on Nov. 15, 1855 in Davidson County.

Unfortunately, what became of Anna is just as mysterious as what became of the servants who lived in her home in southern Scott County when the 1860 census was taken. She simply disappeared, and Gustavus married again in 1866. It seems likely that she died — but of what? And where was she buried?

Some family trees also list another child of Gustavus and Anna — Ellen — who was born and died in 1860.

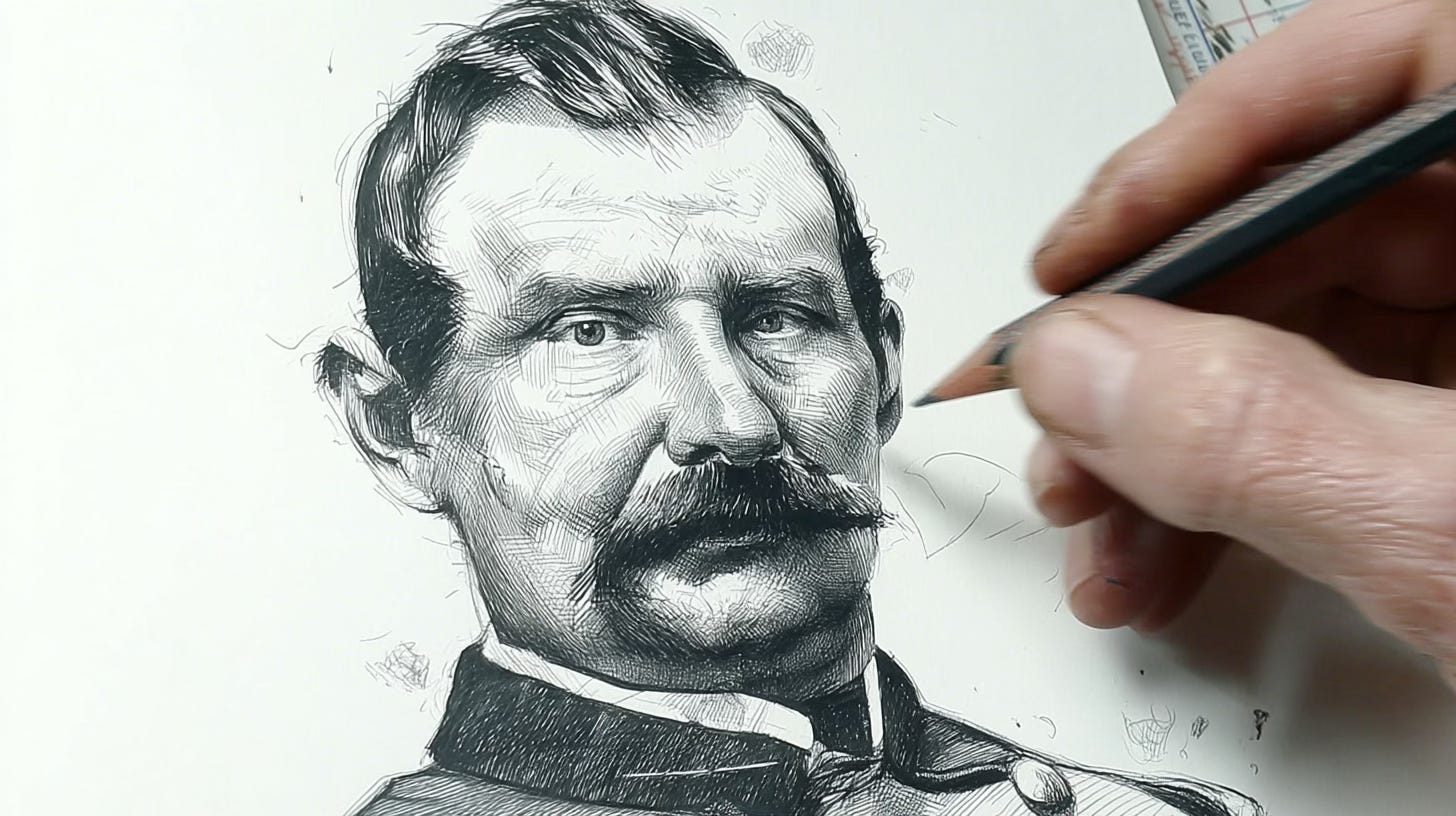

A Union surgeon

When the Civil War began, Gustavus Brandau sided with the Union — as did almost everyone else from Scott County. In May 1863 he enlisted in the federal army at Lebanon, Ky., and mustered into the 11th Tennessee Cavalry in Knoxville, Tenn. as a surgeon. The 11th Tennessee was just being organized at that time, and was commanded by Col. Isham Young. Many of those who served in the 11th Tennessee mustered in at Camp Nelson, Ky. in August 1863.

Little information is available about Brandau’s wartime service, other than that he served until 1865, then mustered out. He is not listed in Paul Roy’s Scott County in the Civil War among the more than 500 others from this community who served in the war, though he apparently should’ve been. We do know from historical records of troop movements that the 11th Tennessee was at Cumberland Gap from October 1863 to February 1864. It was part of Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s assault on the Cumberland Gap after he had marched his Army of the Ohio through Scott County and seized Knoxville from Confederate forces. The 11th Tennessee Cavalry was eventually absorbed by the 9th Tennessee Cavalry in 1865.

Brandau’s remarriage

On May 1, 1866, Gustavus Brandau married Charlotte Caribbean Roehl in Knoxville. She was a 19-year-old German beauty with an origin story that reads like fiction. Her parents, en route from Denmark to California during the 1847 gold rush, had been blown off course by a storm, their ship — Charlotte — winding up in the Caribbean Sea. When their baby girl was born on Christmas Day in 1847, they named her after the voyage itself: Charlotte Caribbean. The family had moved to Knoxville by 1860.

The same week that he married Charlotte, Gustavus represented Scott County as its lone delegate at the East Tennessee Convention in Knoxville. The purpose of the convention was to seek independent statehood for East Tennessee. Records of that week’s convention, and Brandau’s role in it, come from Brownlow’s Knoxville Weekly Whig newspaper. East Tennessee had sought to separate itself from the rest of Tennessee once before — in 1861, after East Tennessee voted against secession but the rest of the state supported secession. Delegates had met in Greeneville in June 1861. Scott County was not represented at the first East Tennessee Convention in person, but was represented by proxy.

The May 1866 convention had the same outcome as the 1861 convention in Greeneville. Delegates argued that East Tennessee was isolated from the rest of the state by the Cumberland Mountains, and that the political differences that had emerged amid the secession fight in 1861 still existed, even though the Civil War was over. But its argument fell on deaf ears in Nashville and Washington, and statehood was not granted.

From Glenmary to Arlington

After the May 1866 convention in Knoxville, the records trail grows faint. We know that Brandau moved to Knoxville permanently; he and Charlotte were living in Knoxville when the 1870 census was taken, along with Brandau’s two children by his first wife, Henry and Alex, and two more sons: Walter R. and Adolph Gustavis. A daughter, Annie, would be born in 1873. Property records place him on Gay Street in Knoxville in August 1866.

Then, in October 1875, Gustavus died. He would’ve only been around 55 at the time but it isn’t clear what he died of. He was buried at Knoxville National Cemetery. But after some time, his body was exhumed, and he was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C.

Charlotte continued living in Knoxville for a time. By 1900, she was living with her daughter, Annie, and her son-in-law in Columbia, Tenn. In 1910, she lived with her son, Adolph, in Nashville. In 1920, she was living with Annie again, this time in Washington, D.C.

It seems the family always had money. Gustavus had employed servants when he lived in Scott County in 1860. His daughter employed servants in 1900, and his son employed servants in 1910.

Charlotte eventually died in 1925, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Adolph lived the remainder of his life in Nashville, while Annie later moved to Florida. Less clear is what happened to Henry, Alex and Walter.

The man and the mystery

So who was Dr. Gustavus Reynard Brandau?

A physician, certainly. A Union soldier, yes. But he was also something harder to pin down: a man between worlds. Between Germany and Tennessee. Between medicine and war. Between one wife and the next. Between the frontier wilds of Glenmary long before it was Glenmary and the marble headstones of Arlington.

The name of his little postal outpost — Fort Brandau — survives only in faint ledgers, a whisper from the forested hills of southern Scott County where coal would later be discovered and give rise to one of the county’s largest late 19th century settlements. Yet in that name lies a story of ambition, reinvention, and a peculiar blending of old-world intellect and new-world grit that defined so many immigrant dreamers of the 19th century.

And yet so little was recorded about his life in America. You can’t help but feel that Gustavus Brandau accomplished something worth remembering during his time in Glenmary. But there’s no record of it. All we’re left with is the wonder of a Hessian surgeon who built himself a fort and left behind a mystery.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletter will be The Daybreaker bright and early Monday morning. If you’d like to update your subscription to add or subtract any of our newsletters, do so here. If you haven’t yet subscribed, it’s as simple as adding your email address!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes from the Past (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)