You’re reading “Echoes in Time,” a weekly newsletter by the Independent Herald that focuses on stories of years gone by in order to paint a portrait of Scott County and its people. “Echoes in Time” is one of six weekly newsletters published by the IH. You can adjust your subscription settings to include as many or as few of these newsletters as you want. If you aren’t a subscriber, please consider doing so. It’s free!

Today’s newsletter is sponsored by the Scott County Chamber of Commerce. Since 1954, the Scott County Chamber of Commerce has advocated for a strong community by supporting stronger infrastructure and leadership.

A long-forgotten post office in the Big South Fork?

Scott County has had as many as 58 post offices through the years. The ones that are in operation today, of course — Oneida, Huntsville, Helenwood, Robbins, Winfield and Elgin — in addition to many that are no longer around because of consolidation through the years.

Most of those post offices are self-expanatory. There was a post office at Alderville, for example, that was established in 1901 and operated until 1914. And one at Wolf Creek that opened in 1869 and operated until 1875.

But some of those post offices are a little more obscure. For example, there was once a post office in Scott County named Walnut Springs. It operated for just two years, from 1866 to 1868. And another Goodwater. And Fogal. And the list goes on.

We recently examined one of those post offices in this space — “Fort Brandon” in the Glenmary area, which was actually named Fort Brandau, and operated by a doctor who later served as a surgeon for the Union army during the Civil War.

But there’s still more about Scott County’s long-past post offices that is unknown ... including, perhaps, a post office located in what is now the Big South Fork National River & Recreation Area that’s been mostly forgotten by time.

Much of what we know about Scott County’s post offices comes from handwritten records of the Post Office Department that are maintained by the National Archives in Washington, D.C. These records list a Frona post office, which began operation in July 1892 and was open until September 1895, when it moved to Oneida.

It’s fairly well-known that there was a post office in the Big South Fork called Elva. It was located first at No Business Creek, with Lewis Burke serving as postmaster when it opened in 1904. It later moved to Station Camp Creek, with Ike King serving as postmaster, and didn’t close until 1935. It was one of the last of Scott County’s backwater post offices to close, and the No Business and Station Camp areas were officially known for years as Elva due to the post office designation.

But, it seems, Elva wasn’t the only post office located in the river settlements. There was Zena Post Office, which was located on No Business Creek with Lewis Burk Jr. serving as postmaster. It was only open for two months, from November 1897 to January 1898. It appears, though, that a third post office can be added to the list: Frona.

Unfortunately, the records don’t list the locations of post offices; only their names and the appointments of postmasters. So we’re left to guess the location of some of the post offices that aren’t well-documented historically, including Frona. And not all of the locations are clear. For example, there was a Parch Corn Post Office that operated in Scott County from March 1877 to January 1892, but it does not appear to have been located on Parch Corn Creek in the Big South Fork, but near Helenwood.

As for Frona, our clues about its location come from its postmasters. When it opened in July 1892, William H. Blevins was serving as postmaster. When it closed in September 1895 and moved to Oneida, William W. Owens was serving as postmaster.

These men were likely William Huston “Huse” Blevins and William “Wesley” Owens; census records from that era don’t offer any other possibilities.

Huse and Wesley both lived at the Big South Fork during that time. Huse’s family lived on Parch Corn Creek, and Wesley’s family lived just up the river at Station Camp Creek.

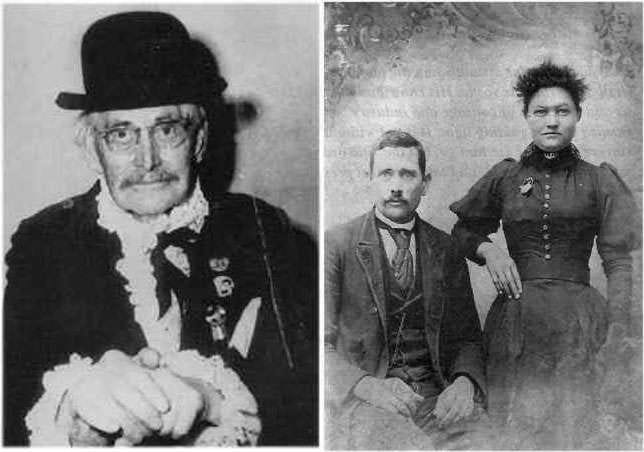

Huse Blevins would go on to become a very well-known Scott Countian. The son of Armstead Blevins and Hellen Terry, he was a product of Big South Fork’s pioneer families. His paternal grandfather was Jonathan Blevins, often referred to (most likely incorrectly) as the first settler of Station Camp Creek. His maternal grandfather was Elijah Terry, the first settler of Parch Corn Creek. It was on Elijah Terry’s farm that the Blevins family lived after Armstead married Hellen, who was Elijah’s daughter. (Elijah’s brother, Josiah Terry, was the first settler of Oneida; they moved here together from Virginia.)

Blevins left the Big South Fork at the age of 20 to enroll at Huntsville Academy, where he fed livestock and did other odd jobs to pay for his room and board. He went on to teach school and held many other positions, including justice of the peace (a forerunner to what we know as county commissioner today), was a deputy sheriff, a constable, and superintendent of a lumber company. One of his last positions in education was as principal of Rock Creek School near Oneida. He was also a noted politician, fiercely loyal to the Republican Party. He campaigned for every Republican candidate for president from 1896 until he retired in the 1960s.

In 1892, Blevins would have been only 23 years old. But, according to records, he still lived with his mother and some of his siblings on Parch Corn Creek. (He would later marry into the Marcum family and move to Pine Creek just outside Oneida.)

Twenty-three would have been young to be a postmaster, by Scott County’s historical standards. But there was little that was ordinary about Huse Blevins, who traded a catfish for a math book at the age of 10 so that he could learn to decipher.

Wesley Owens is one of the Big South Fork’s most tragic stories. He was not from Big South Fork pioneer stock; rather, he married into it. His second wife was Susannah Slaven, the granddaughter of Richard Harve Slaven, who was the first settler at No Business Creek. (Owens appears to have first been married to Elizabeth Roysden and had several children with her, though it’s not apparent what became of his first family.)

Owens and Slaven married in 1877, and moved to Station Camp Creek, settling on a wide spot in the creek valley about 1.5 miles west of the Big South Fork River. There, he operated a grist mill and a blacksmith shop. What really made Wesley Owens notable is the cemetery on a small ridge overlooking his fields, where he buried many of his children.

The Owens Cemetery is quite a story of tragedy. Over a period of 12 years, Wesley Owens buried seven of his children in a single row of graves on the rocky hillside — and then he was buried there himself when he died in 1903.

It’s not completely clear what claimed the lives of all the Owens children. The late archaeologist Tom Des Jean, who worked for the Big South Fork National River & Recreation Area for many years, speculated that they lost their lives during waves of virus that spread throughout the Big South Fork river settlements in the 1880s and 1890s. The first to die was 13-year-old Samantha in 1888, followed by 11-year-old James just a few months later, 4-year-old Sarah in 1889, 9-year-old Lawrence in 1892, 7-year-old Electa in 1896, and 7-year-old George in 1900. At some point prior to 1900, Ebbin, the second-oldest child of the family, also died.

Following Wesley’s death in 1903, Susannah — whose first husband, Dan Pennington, had been shot and killed by her brothers during a dispute — left the Big South Fork and moved to Wayne County, Ky. Her three surviving children — Willis, Cordelia and Baily — are all buried at Possum Rock Cemetery in the Black Oak community.

Wesley Owens would have been 70 in September 1895, when the Frona Post Office closed.

There’s no solid evidence to indicate that Frona was located in the Big South Fork. But the names fit. William H. Blevins and William W. Owens were neighbors on the river in those days. And they were close acquaintances. When Owens wrote his will shortly before his death in 1903, Blevins signed it as one of the witnesses.

What’s less clear is where the name Frona would’ve come from. Traditionally, post offices took their name from their location (such as Alderville and Wolf Creek) or the person who established them (such as Fort Brandau). But the Station Camp/Parch Corn Creek area was not known as Frona, and Blevins didn’t have any children named Frona (he didn’t have any children at all in 1892).

By 1895, things were beginning to change in the river settlements, as coal and timber operations slowly eroded the subsistence lifestyle that had dominated the region for nearly 100 years. Within another generation, families would begin leaving the river settlements once and for all. In 1901, Huse Blevins married Rosa Marcum and became one of the first among his family to leave, moving to Pine Creek. Wesley Owens died in 1903 and Susannah left for Mt. Pisgah, Ky. Jacob Blevins Jr., who lived up the creek a little further and was one of Huse’s first cousins, operated the mill on the Owens farm for a while, but it eventually closed.

It isn’t clear how the postal needs of the communities along the river were served between 1895 and when the Elva Post Office was established downriver at No Business a decade later. But it does appear that Frona was the Big South Fork region’s first post office.

Thank you for reading. Our next newsletters will be Threads of Life on Wednesday and The Weekender Thursday evening. Want to update your subscription to add or subtract these newsletters? Do so here. Need to subscribe? Enter your email address below!

◼️ Monday morning: The Daybreaker (news & the week ahead)

◼️ Tuesday: Echoes in Time (stories of our history)

◼️ Wednesday: Threads of Life (obituaries)

◼️ Thursday evening: The Weekender (news & the weekend)

◼️ Friday: Friday Features (beyond the news)

◼️ Sunday: Varsity (a weekly sports recap)

Interesting my friend and writer Mr. Sam Perry (his family_ Thanks again